Study Notes

Overview

Fractional distillation is a cornerstone of the chemical industry and a topic that frequently appears in Edexcel GCSE Chemistry exams. It is the industrial process used to separate crude oil, a complex mixture of hydrocarbons, into simpler, more useful mixtures called fractions. Understanding this process is not just about memorising the order of fractions; it's about grasping the fundamental principles of intermolecular forces and boiling points. In your exam, you can expect questions that ask you to describe the process, explain the science behind it, and link the properties of different fractions to their uses. This guide will equip you with the knowledge and exam technique to tackle any question on fractional distillation with confidence.

Key Concepts

Concept 1: Crude Oil as a Mixture of Hydrocarbons

Crude oil is a fossil fuel formed from the remains of ancient marine organisms over millions of years. It is a complex mixture containing hundreds of different hydrocarbons – molecules made up of hydrogen and carbon atoms only. These hydrocarbons exist in a vast range of sizes, from small molecules with just one carbon atom (like methane) to giant molecules with over 70 carbon atoms (found in bitumen). It is this variation in size that allows us to separate them.

Concept 2: The Principle of Separation by Boiling Point

Fractional distillation works because the different hydrocarbons in crude oil have different boiling points. This is directly related to the size of the molecules:

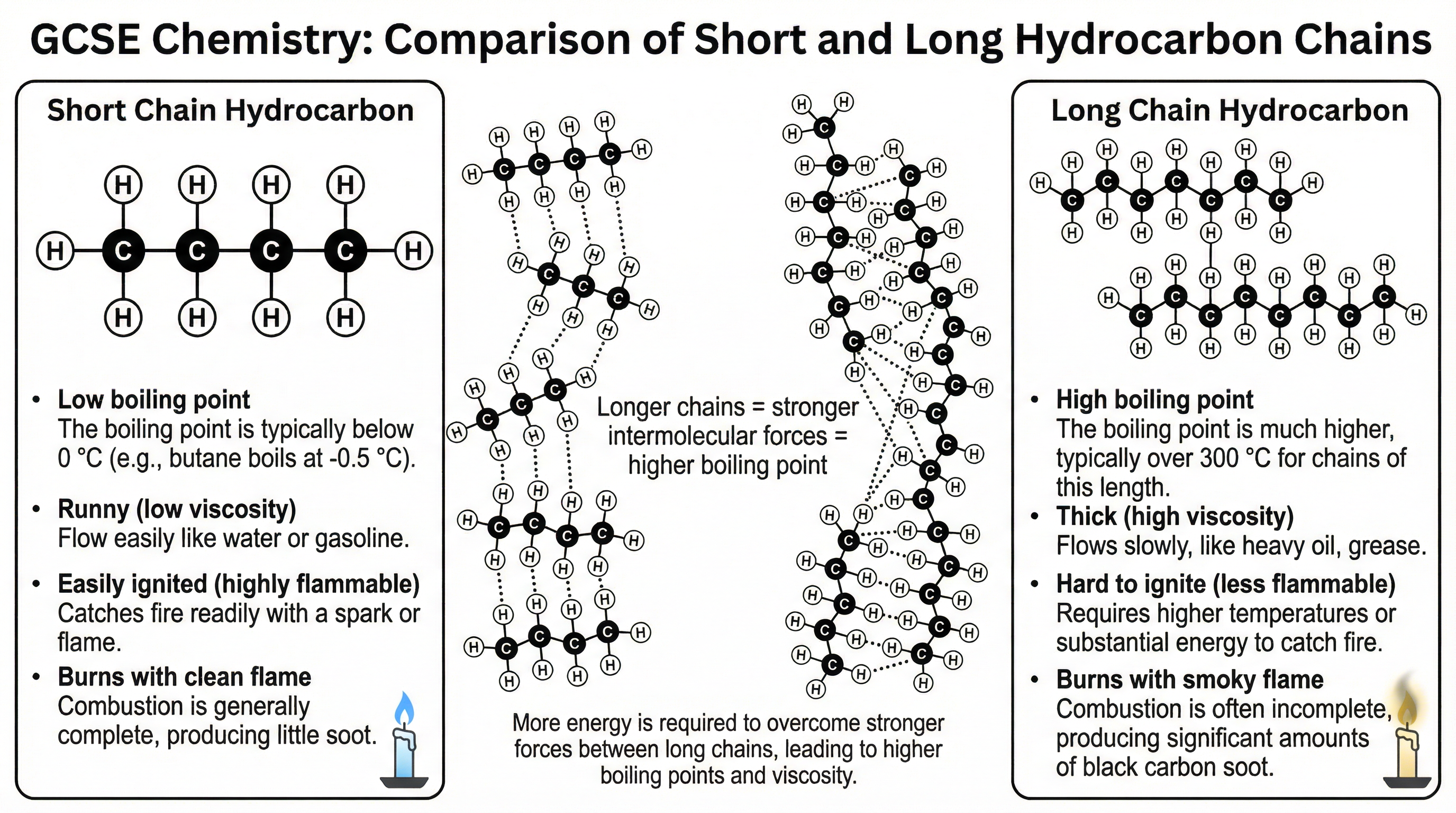

- Short-chain hydrocarbons: These have few carbon atoms. The intermolecular forces (weak forces of attraction between the molecules) are weak. Consequently, little energy is needed to overcome these forces, resulting in low boiling points. They are volatile, runny (low viscosity), and highly flammable.

- Long-chain hydrocarbons: These have many carbon atoms. The intermolecular forces between these large molecules are much stronger. A great deal of energy is required to overcome these forces, leading to high boiling points. They are thick (viscous), not very volatile, and less flammable.

It is a common mistake to think that covalent bonds inside the hydrocarbon molecules are broken during this process. Examiners are very clear: credit is only given for answers that correctly identify the overcoming of intermolecular forces between molecules.

Concept 3: The Fractionating Column

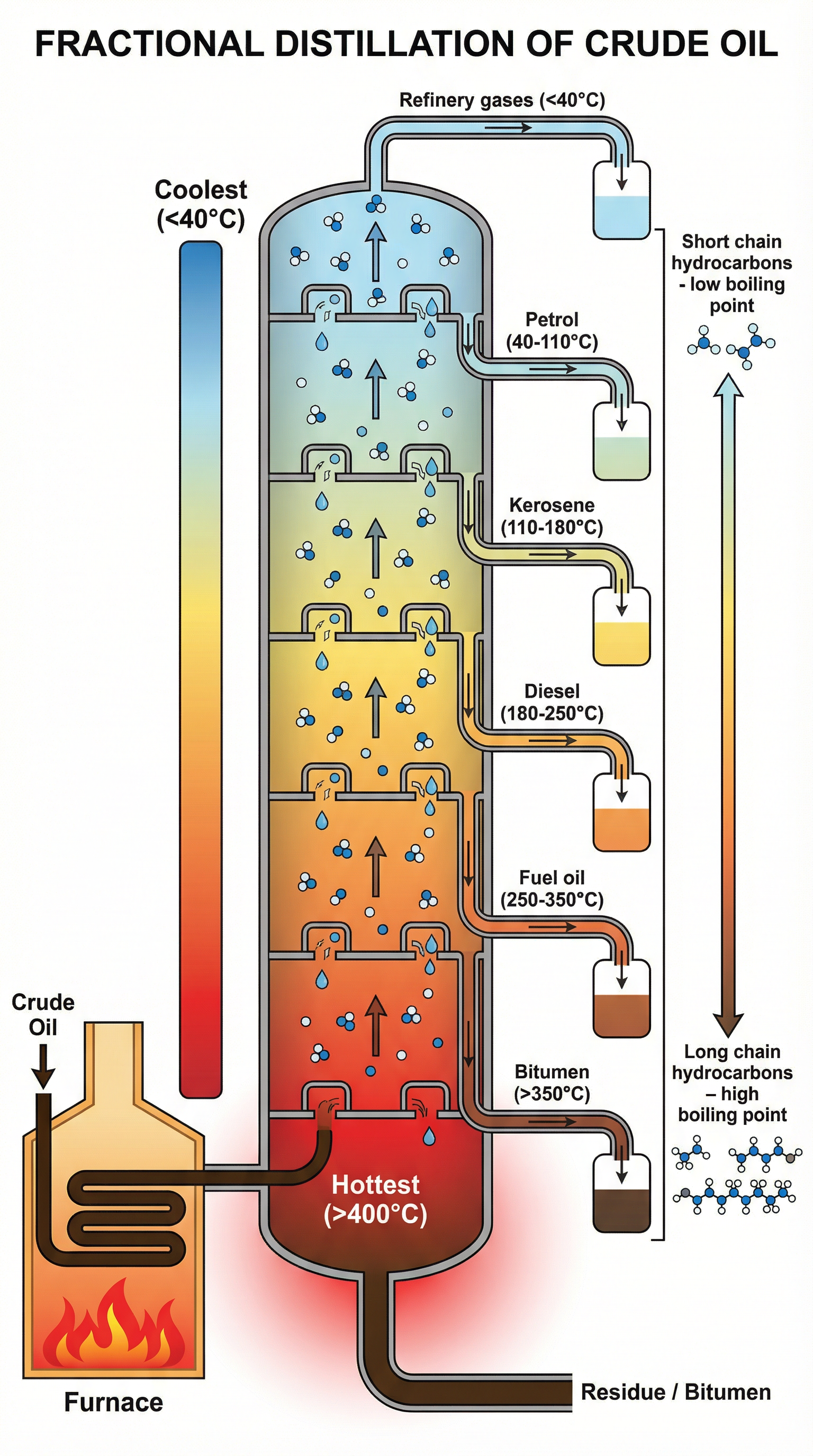

The separation is carried out in a fractionating column, which can be over 40 metres tall. The column has a temperature gradient, a critical term that you must use in your exam answers. It is very hot at the bottom (around 400°C) and gradually gets cooler towards the top (around 25°C).

Here is the step-by-step process:

- Heating: Crude oil is heated in a furnace to a high temperature, causing most of the hydrocarbons to vaporise (turn into a gas).

- Vapours Enter the Column: The hot mixture of liquid and vapour is pumped into the bottom of the fractionating column.

- Rising and Cooling: The hot vapours rise up the column. As they rise, they cool down.

- Condensing: When a hydrocarbon vapour reaches a level in the column where the temperature is equal to or below its boiling point, it condenses (turns back into a liquid). The condensed liquid is collected on trays at different levels.

- Collection of Fractions: Shorter chain hydrocarbons with low boiling points continue to rise higher up the column before they condense. The longest chain hydrocarbons with very high boiling points may not vaporise at all and are collected at the bottom as a thick liquid residue.

The Main Fractions and Their Uses

It is essential to memorise the main fractions in order, from top to bottom, and know their primary uses.

| Fraction | Approx. Boiling Range (°C) | No. of Carbon Atoms | Primary Use(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refinery Gases | < 40 | 1 - 4 | Bottled gas (LPG) for heating and cooking |

| Petrol (Gasoline) | 40 - 110 | 5 - 12 | Fuel for cars |

| Kerosene | 110 - 180 | 11 - 15 | Fuel for jet engines, paraffin for lamps |

| Diesel Oil (Gas Oil) | 180 - 250 | 15 - 19 | Fuel for diesel engines (lorries, trains) |

| Fuel Oil | 250 - 350 | 20 - 40 | Fuel for ships, power stations, central heating |

| Bitumen | > 350 | > 40 | Surfacing roads, roofing felt |

Mathematical/Scientific Relationships

There are no complex mathematical formulas to learn for this topic at GCSE. The key relationship is conceptual:

**Chain Length ↑ → Intermolecular Forces ↑ → Boiling Point ↑ → Viscosity ↑ → Flammability ↓**This means as the hydrocarbon chain length increases, the strength of the intermolecular forces increases, which in turn increases the boiling point and viscosity, while making the substance less flammable. You must be able to state and explain these trends.

Practical Applications

This entire topic is a real-world application. The products of fractional distillation power our transport, heat our homes, and build our infrastructure. While there isn't a specific required practical on fractional distillation of crude oil (it's too dangerous and complex for a school lab), you may perform a simpler distillation to separate a mixture like ink and water. The principles are the same: separation based on a difference in boiling points. Examiners can ask you to apply your understanding of laboratory distillation to the industrial process.