Study Notes

Overview

Welcome to the fascinating world of reversible reactions, a cornerstone of chemistry that explains everything from industrial processes to biological systems. In this guide, we will explore the dynamic nature of chemical equilibrium. Unlike reactions that go to completion, reversible reactions can proceed in both the forward and backward directions. We will represent this using the special equilibrium symbol (⇌) and investigate the conditions required for a system to reach a state of dynamic equilibrium. For Foundation tier candidates, the focus will be on identifying reversible reactions and understanding key examples like the thermal decomposition of ammonium chloride. For Higher tier candidates, we will delve into the powerful predictive tool known as Le Chatelier's Principle, which allows us to determine how changes in temperature, pressure, and concentration affect the position of equilibrium. This topic is frequently tested through structured questions that require clear, logical explanations, and a solid grasp of these concepts is essential for achieving a high grade.

Key Concepts

Concept 1: Reversible Reactions

A reversible reaction is a chemical reaction where the products can react to re-form the original reactants. This is distinct from most reactions you have studied, which are irreversible. We use a double arrow symbol (⇌) to indicate that a reaction is reversible.

Example: The reaction between nitrogen and hydrogen to form ammonia in the Haber process is a classic reversible reaction.

N₂(g) + 3H₂(g) ⇌ 2NH₃(g)

This equation tells us that nitrogen and hydrogen can react to form ammonia (the forward reaction), and ammonia can decompose back into nitrogen and hydrogen (the backward reaction).

Another key example is the dehydration of hydrated copper(II) sulfate. When blue hydrated copper(II) sulfate crystals are heated, they lose their water of crystallisation and turn into white anhydrous copper(II) sulfate powder. This is the forward reaction. If water is then added to the white powder, it turns blue again, reforming the hydrated crystals. This is the backward reaction.

CuSO₄·5H₂O(s) (blue) ⇌ CuSO₄(s) (white) + 5H₂O(l)

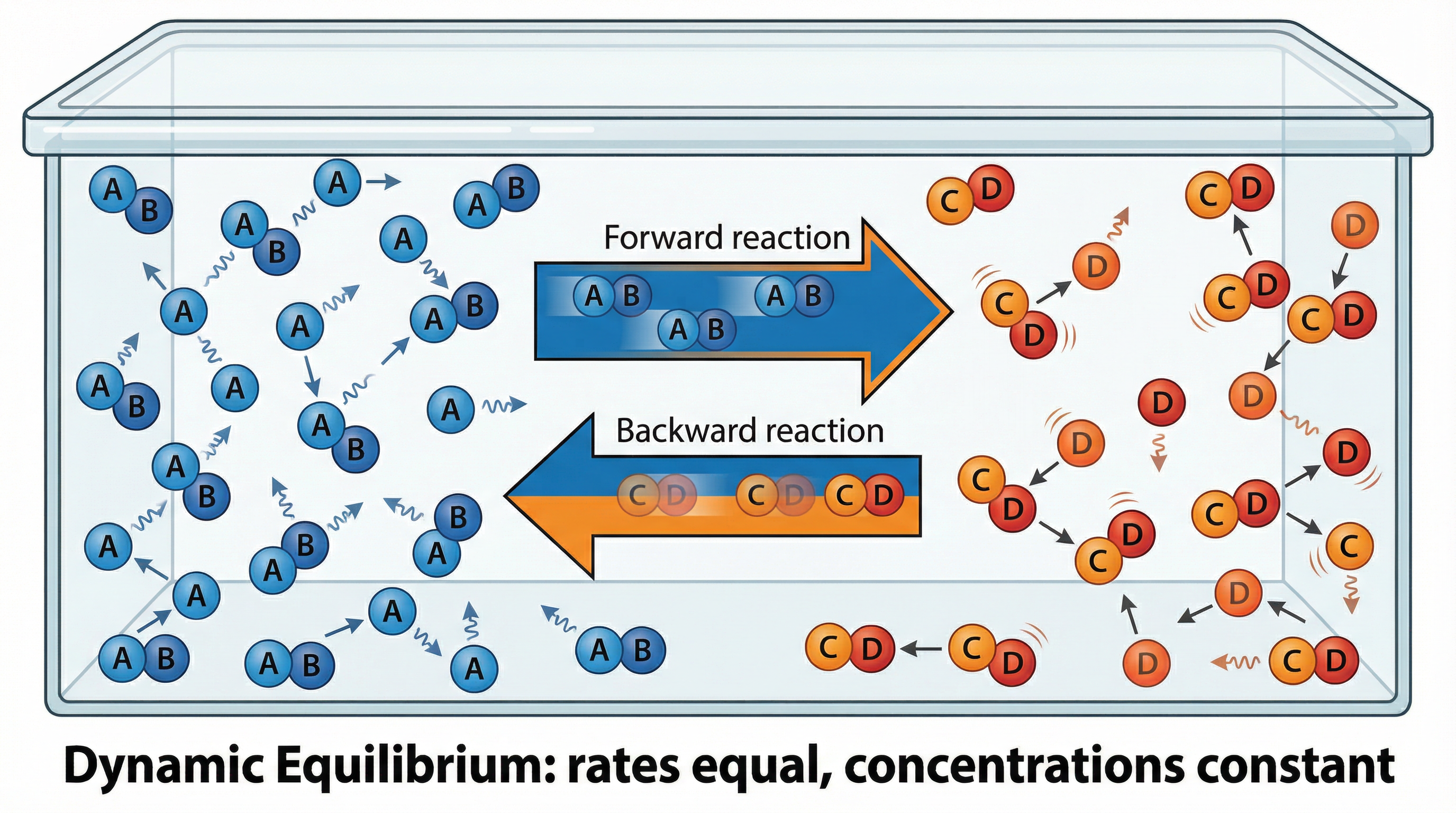

Concept 2: Dynamic Equilibrium

In a closed system, a reversible reaction will eventually reach a state of dynamic equilibrium. A closed system is one where no substances can enter or leave. At equilibrium, the rate of the forward reaction is exactly equal to the rate of the backward reaction. It is crucial to understand that the reactions have not stopped; they are still occurring continuously. This is why it is called dynamic. Because the rates are equal, the overall concentrations of the reactants and products remain constant. It is a common misconception that the concentrations of reactants and products are equal at equilibrium; this is rarely the case. The concentrations are simply no longer changing.

Key conditions for dynamic equilibrium:

- It must be a reversible reaction.

- The system must be closed.

- The macroscopic properties (like colour, pressure, concentration) are constant.

- The rate of the forward reaction equals the rate of the backward reaction.

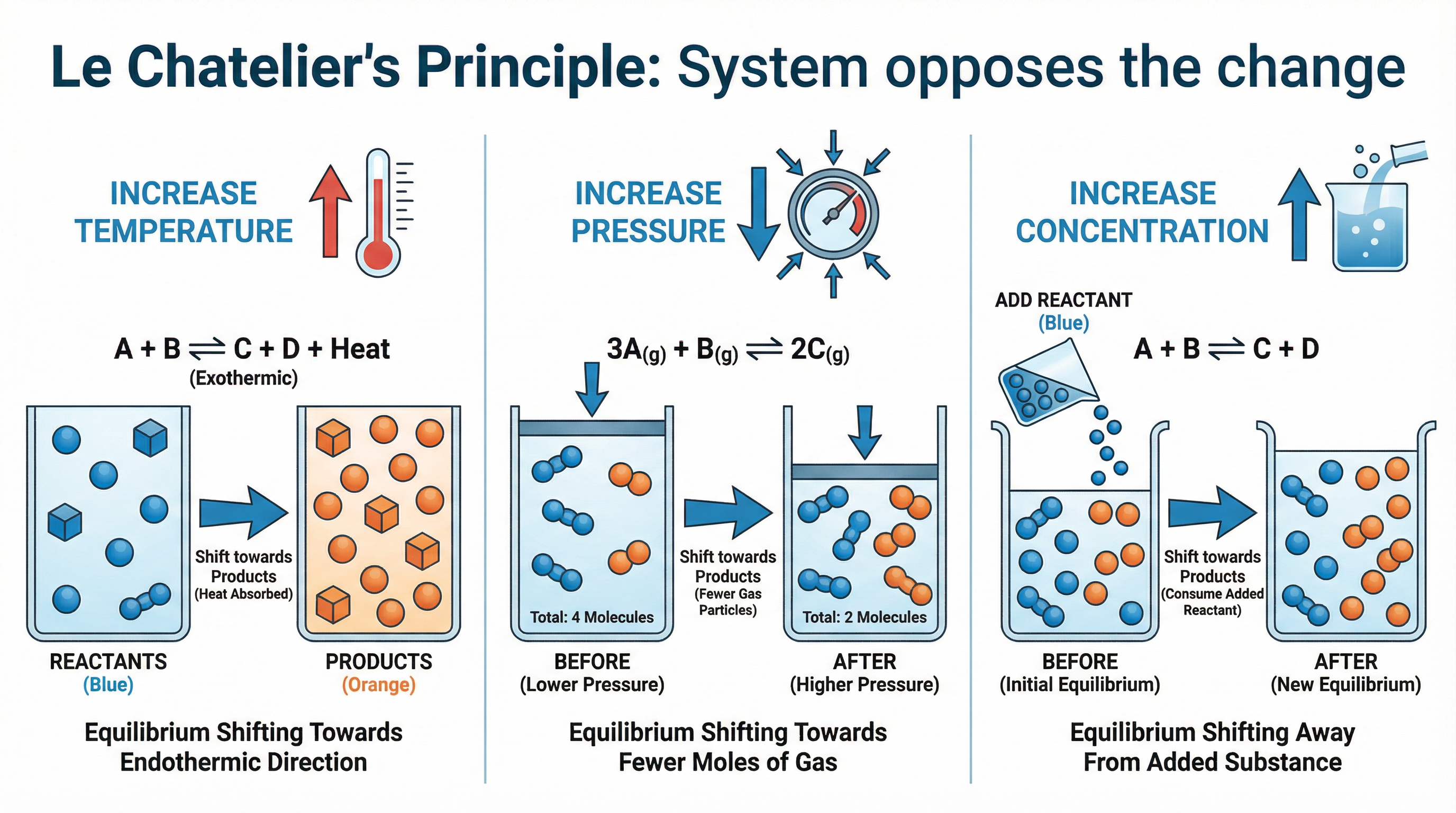

Concept 3: Le Chatelier's Principle (Higher Tier Only)

Le Chatelier's Principle is a powerful tool for predicting how a system at equilibrium will respond to a change in conditions. It states that if a change is made to a system at equilibrium, the system will respond by partially opposing the change.

The Effect of Temperature

If you increase the temperature of a system at equilibrium, the system will try to cool itself down by favouring the reaction that absorbs heat. This is the endothermic reaction. If you decrease the temperature, the system will try to warm itself up by favouring the reaction that releases heat, which is the exothermic reaction.

- Increase Temperature: Equilibrium shifts in the endothermic direction (ΔH is positive).

- Decrease Temperature: Equilibrium shifts in the exothermic direction (ΔH is negative).

The Effect of Pressure

Changes in pressure only affect reactions involving gases. If you increase the pressure on a system at equilibrium, the system will try to reduce the pressure by favouring the reaction that produces fewer moles of gas. If you decrease the pressure, the system will favour the reaction that produces more moles of gas.

- Increase Pressure: Equilibrium shifts to the side with fewer moles of gas.

- Decrease Pressure: Equilibrium shifts to the side with more moles of gas.

Important: To determine the effect of pressure, you must count the total number of moles of gaseous molecules on each side of the equation. If the number of moles of gas is the same on both sides, a change in pressure will have no effect on the position of equilibrium.

The Effect of Concentration

If you increase the concentration of a reactant, the system will try to use it up by favouring the forward reaction, shifting the equilibrium to the right. If you increase the concentration of a product, the system will try to remove it by favouring the backward reaction, shifting the equilibrium to the left.

- Increase Reactant Concentration: Equilibrium shifts to the right (products).

- Increase Product Concentration: Equilibrium shifts to the left (reactants).

The Effect of a Catalyst

A catalyst increases the rate of both the forward and backward reactions equally. Therefore, a catalyst does not change the position of equilibrium. It only allows equilibrium to be reached faster.

Mathematical/Scientific Relationships

There are no complex mathematical formulas to memorise for this topic at GCSE level. The key relationships are conceptual:

- Equilibrium: Rate(forward) = Rate(backward)

- Le Chatelier's Principle (Higher Tier):

- Temperature: ↑T favours endothermic; ↓T favours exothermic.

- Pressure: ↑P favours fewer gas moles; ↓P favours more gas moles.

- Concentration: ↑[Reactant] favours products; ↑[Product] favours reactants.

Practical Applications

Understanding reversible reactions is vital for industrial chemistry. The Haber Process, used to manufacture ammonia for fertilisers, is a prime example. The reaction N₂(g) + 3H₂(g) ⇌ 2NH₃(g) is reversible and exothermic. Industrial chemists apply Le Chatelier's Principle to maximise the yield of ammonia. They use high pressure (to favour the side with fewer gas moles) and a compromise temperature. A low temperature would favour the exothermic forward reaction, but it would also make the reaction too slow. Therefore, a moderately high temperature (around 450°C) and an iron catalyst are used to achieve a reasonable rate and a decent yield.