Study Notes

Overview

Atomic Structure sits at the very heart of chemistry. Understanding how protons, neutrons, and electrons are arranged within an atom allows us to predict and explain the chemical properties of every element on the periodic table. This topic covers the quantum mechanical model of the atom, including shells, sub-shells, and orbitals, as well as the critical concepts of relative atomic mass and ionisation energy. OCR examiners test this topic rigorously through precise definitions, electron configuration questions, calculations involving isotopic abundance, and explanations of periodic trends. Typical exam questions include writing electron configurations for atoms and ions, explaining anomalies in ionisation energy trends across periods, and calculating relative atomic mass from mass spectrometry data. This topic also provides synoptic links to bonding, periodicity, and transition metal chemistry, making it one of the most important foundations for A-Level success.

Key Concepts

Concept 1: Relative Atomic Mass and Isotopes

Atoms of the same element can have different numbers of neutrons, creating isotopes. These isotopes have the same chemical properties because they have the same number of electrons, but they have different physical properties due to their different masses. The relative isotopic mass is defined as the mass of an atom of an isotope compared with 1/12th of the mass of an atom of carbon-12. This is a straightforward comparison for a single isotope.

However, most elements exist as a mixture of isotopes in nature. To account for this, we use relative atomic mass (Ar), which is the weighted mean mass of an atom of an element compared with 1/12th of the mass of an atom of carbon-12. The phrase 'weighted mean mass' is absolutely critical in the definition because it indicates that we must take into account both the mass and the abundance of each isotope. OCR examiners will not award the mark if you omit this phrase.

To calculate relative atomic mass from isotopic data, you multiply each isotopic mass by its percentage abundance, sum all the results, and divide by 100. For example, chlorine has two main isotopes: Cl-35 (75% abundance) and Cl-37 (25% abundance). The relative atomic mass is calculated as: Ar = (35 × 75 + 37 × 25) / 100 = 35.5. Always pay attention to the number of significant figures or decimal places specified in the question.

Example: Copper has two isotopes: Cu-63 (69.2% abundance) and Cu-65 (30.8% abundance). Calculate the relative atomic mass of copper.

Ar = (63 × 69.2 + 65 × 30.8) / 100 = (4359.6 + 2002) / 100 = 6361.6 / 100 = 63.616 ≈ 63.6 (to 3 significant figures).

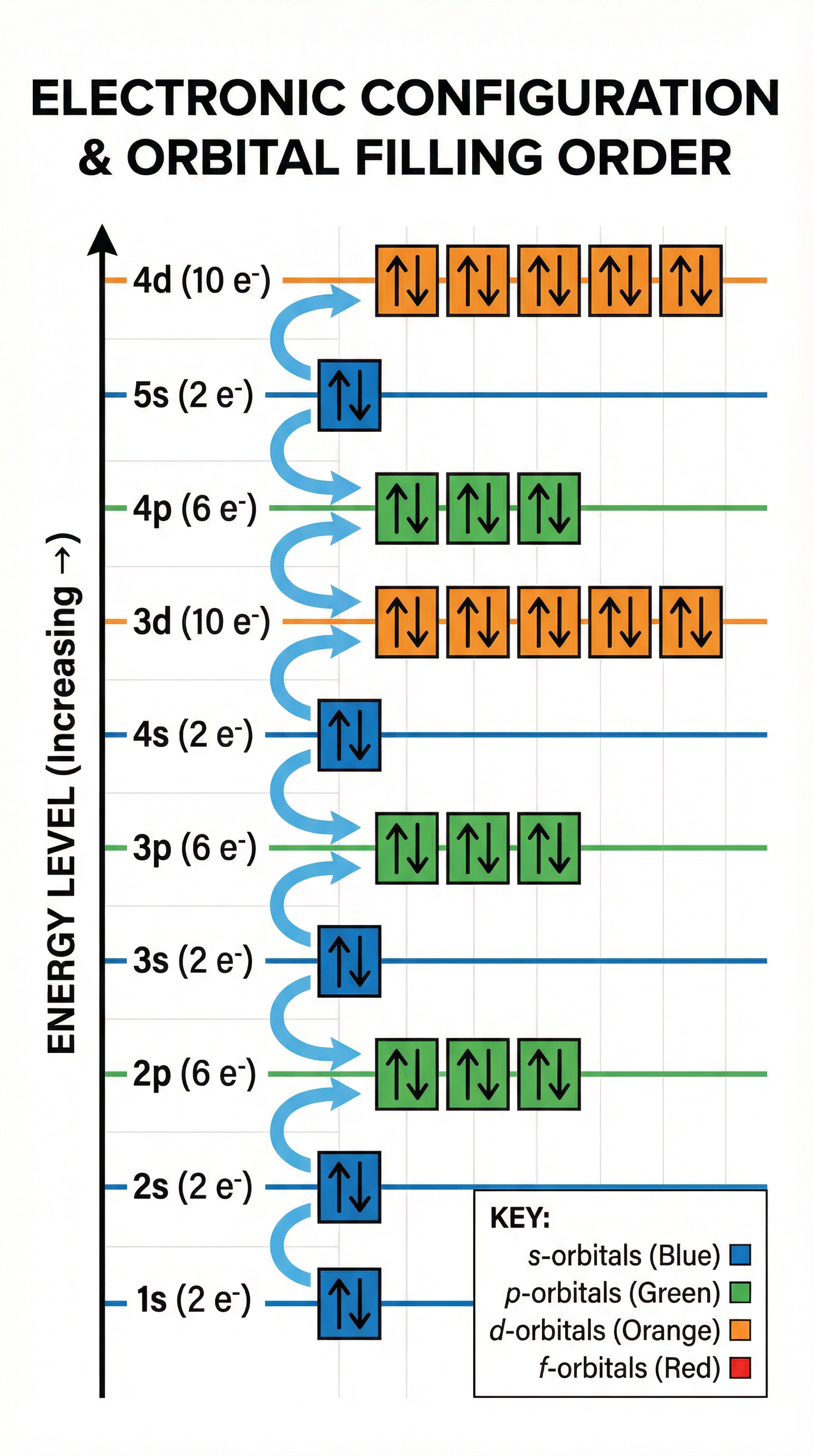

Concept 2: Electronic Configuration and Orbital Filling

Electrons in atoms are arranged in shells (principal energy levels) and sub-shells (s, p, d, f). Each sub-shell contains one or more orbitals, and each orbital can hold a maximum of two electrons with opposite spins. The s sub-shell has 1 orbital (max 2 electrons), the p sub-shell has 3 orbitals (max 6 electrons), the d sub-shell has 5 orbitals (max 10 electrons), and the f sub-shell has 7 orbitals (max 14 electrons).

Electrons fill orbitals according to three key principles. The Aufbau principle states that electrons occupy the lowest available energy level first. Hund's rule states that electrons will occupy orbitals singly before pairing up, to minimise electron-electron repulsion. The Pauli exclusion principle states that no two electrons in the same atom can have the same set of four quantum numbers, which in practice means that each orbital can hold a maximum of two electrons with opposite spins (represented by up and down arrows).

The order of filling is generally: 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, 4p, 5s, 4d, 5p, 6s, 4f, 5d, 6p, 7s, 5f, 6d. Notice that the 4s sub-shell fills before the 3d sub-shell because it is at a slightly lower energy level. However, when electrons are removed to form positive ions, the 4s electrons are removed first, even though they were added first. This is a common source of error in exams.

Example: Write the full electronic configuration for Calcium (Ca, atomic number 20) and for the Ca²⁺ ion.

Ca: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 4s²

Ca²⁺: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ (the two 4s electrons are removed)

Concept 3: d-Block Anomalies (Chromium and Copper)

Most transition metals follow the expected pattern of filling the 4s sub-shell before the 3d sub-shell. However, Chromium (Cr) and Copper (Cu) are exceptions. These elements achieve greater stability by promoting one electron from the 4s sub-shell to the 3d sub-shell.

For Chromium (atomic number 24), the expected configuration would be [Ar] 3d⁴ 4s². However, the actual configuration is [Ar] 3d⁵ 4s¹. This gives a half-filled d sub-shell, which is particularly stable due to symmetrical distribution of electrons and minimised repulsion.

For Copper (atomic number 29), the expected configuration would be [Ar] 3d⁹ 4s². However, the actual configuration is [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s¹. This gives a fully filled d sub-shell, which is also particularly stable.

These anomalies are frequently tested in OCR exams, and candidates must memorise them. When forming ions, remember that the 4s electrons are always removed first. So, Cr²⁺ is [Ar] 3d⁴ (not [Ar] 3d³ 4s¹), and Cu²⁺ is [Ar] 3d⁹ (not [Ar] 3d⁷ 4s²).

Concept 4: Ionisation Energy and Periodic Trends

First ionisation energy is defined as the energy required to remove one mole of electrons from one mole of gaseous atoms to form one mole of gaseous 1+ ions. It is measured in kJ mol⁻¹ and is always an endothermic process (positive energy change). The equation for the first ionisation of sodium is: Na(g) → Na⁺(g) + e⁻.

Ionisation energy is influenced by three main factors: nuclear charge (the number of protons in the nucleus), atomic radius (the distance between the nucleus and the outer electron), and electron shielding (the repulsion between inner shell electrons and the outer electron being removed). A higher nuclear charge and smaller atomic radius increase ionisation energy, while greater shielding decreases it.

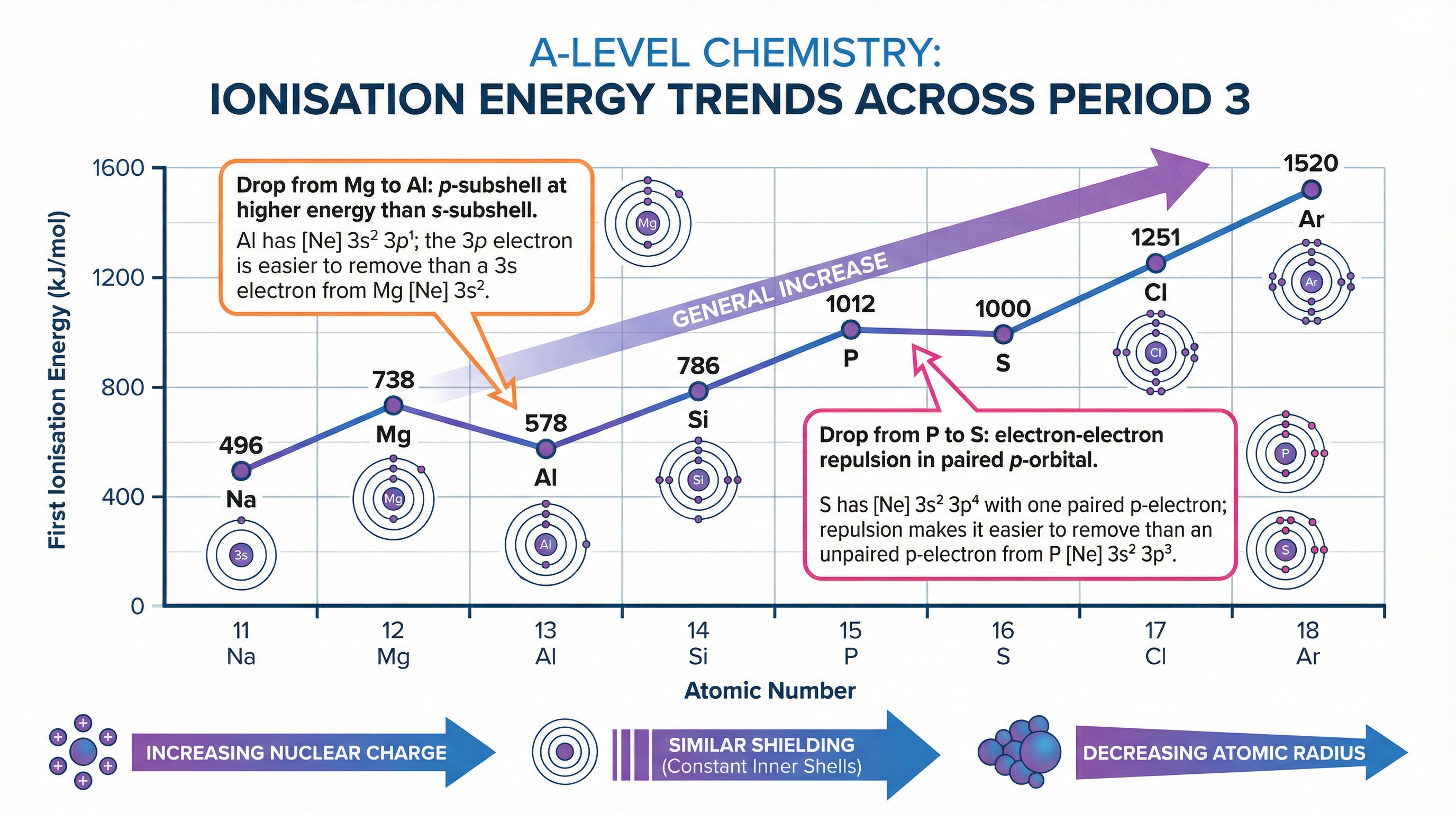

The general trend across a period (left to right) is that ionisation energy increases. This is because nuclear charge increases, atomic radius decreases, and shielding remains broadly constant. The outer electron is therefore more strongly attracted to the nucleus and requires more energy to remove.

The general trend down a group is that ionisation energy decreases. This is because the number of shells increases, so atomic radius increases and shielding increases. These factors outweigh the increase in nuclear charge, so the outer electron is less strongly attracted and easier to remove.

However, there are two important anomalies in the trend across Period 3. The first ionisation energy of Aluminium (Group 3) is lower than that of Magnesium (Group 2). This is because the electron being removed from Aluminium is in a 3p orbital, which is at a higher energy level and slightly further from the nucleus than the 3s orbital in Magnesium. The second anomaly is that the first ionisation energy of Sulfur (Group 6) is lower than that of Phosphorus (Group 5). This is because in Sulfur, the electron is being removed from a paired 3p orbital. The electron-electron repulsion within this paired orbital makes it easier to remove one of the electrons.

Concept 5: Successive Ionisation Energies

Successive ionisation energies refer to the energy required to remove electrons one by one from an atom or ion. The second ionisation energy is the energy required to remove one mole of electrons from one mole of gaseous 1+ ions to form one mole of gaseous 2+ ions, and so on.

Successive ionisation energies always increase because each time an electron is removed, the remaining electrons experience a greater effective nuclear charge (there are fewer electrons to share the same positive charge from the nucleus). Additionally, when an electron is removed from a shell closer to the nucleus, there is a large jump in ionisation energy. This is because inner shell electrons are much more strongly attracted to the nucleus and experience less shielding.

Successive ionisation energy data can be used to deduce the group of an element. For example, if there is a large jump between the second and third ionisation energies, this suggests the element is in Group 2, because the first two electrons are removed from the outer shell, but the third electron must be removed from a shell closer to the nucleus.

Mathematical/Scientific Relationships

Calculating Relative Atomic Mass:

Ar = Σ (isotopic mass × percentage abundance) / 100

Where Σ means 'sum of' for all isotopes present.

First Ionisation Energy Equation:

X(g) → X⁺(g) + e⁻

Where X is any gaseous atom.

Second Ionisation Energy Equation:

X⁺(g) → X²⁺(g) + e⁻

All ionisation energies are endothermic (positive ΔH values).

Key Formulas to Memorise:

- Relative Atomic Mass (Ar): weighted mean mass compared to 1/12th of C-12 (definition, not a calculation formula)

- Relative Isotopic Mass: mass of one isotope compared to 1/12th of C-12

- First Ionisation Energy: energy to remove 1 mole of electrons from 1 mole of gaseous atoms

Note: These definitions are not provided on the formula sheet and must be memorised exactly as specified by OCR.

Practical Applications

Mass Spectrometry: This technique is used to determine the relative isotopic masses and abundances of isotopes in a sample. A mass spectrum shows peaks corresponding to different isotopes, with the height of each peak proportional to the abundance. This data is used to calculate the relative atomic mass of an element. Understanding how to interpret mass spectra and perform these calculations is a key skill tested in OCR exams.

Flame Tests and Emission Spectra: When electrons in atoms are excited (by heat or electricity), they move to higher energy levels. When they fall back down to lower energy levels, they emit energy as light of specific wavelengths. This produces characteristic colours in flame tests and line spectra in emission spectroscopy. The existence of discrete lines (rather than a continuous spectrum) provides evidence for the quantised nature of electron energy levels.

Predicting Reactivity: The ionisation energy of an element gives us insight into how easily it will lose electrons and form positive ions. Elements with low first ionisation energies (such as Group 1 metals) are highly reactive because they readily lose their outer electron. This links directly to the reactivity series and redox chemistry.

Transition Metal Chemistry: Understanding electron configurations, especially the filling and emptying of the d sub-shell, is essential for explaining the properties of transition metals, including their variable oxidation states, coloured compounds, and catalytic behaviour.