Study Notes

Overview

Redox reactions are a cornerstone of chemistry, describing the simultaneous processes of reduction and oxidation. For your OCR GCSE exam, a solid grasp of this topic is crucial as it underpins other key areas like electrolysis, the reactivity series, and chemical cells. Examiners frequently test redox by asking candidates to define the key terms, construct half-equations, and identify the oxidising and reducing agents in a given reaction. This guide will equip you with the two essential models for understanding redox: the simple oxygen transfer model for Foundation Tier, and the more powerful electron transfer model for Higher Tier. By mastering both, you can confidently tackle any redox question the exam throws at you.

Key Concepts

Concept 1: Redox in Terms of Oxygen (Foundation Tier)

The most straightforward way to understand redox is by tracking the movement of oxygen. This definition is sufficient for Foundation Tier candidates and provides a great starting point.

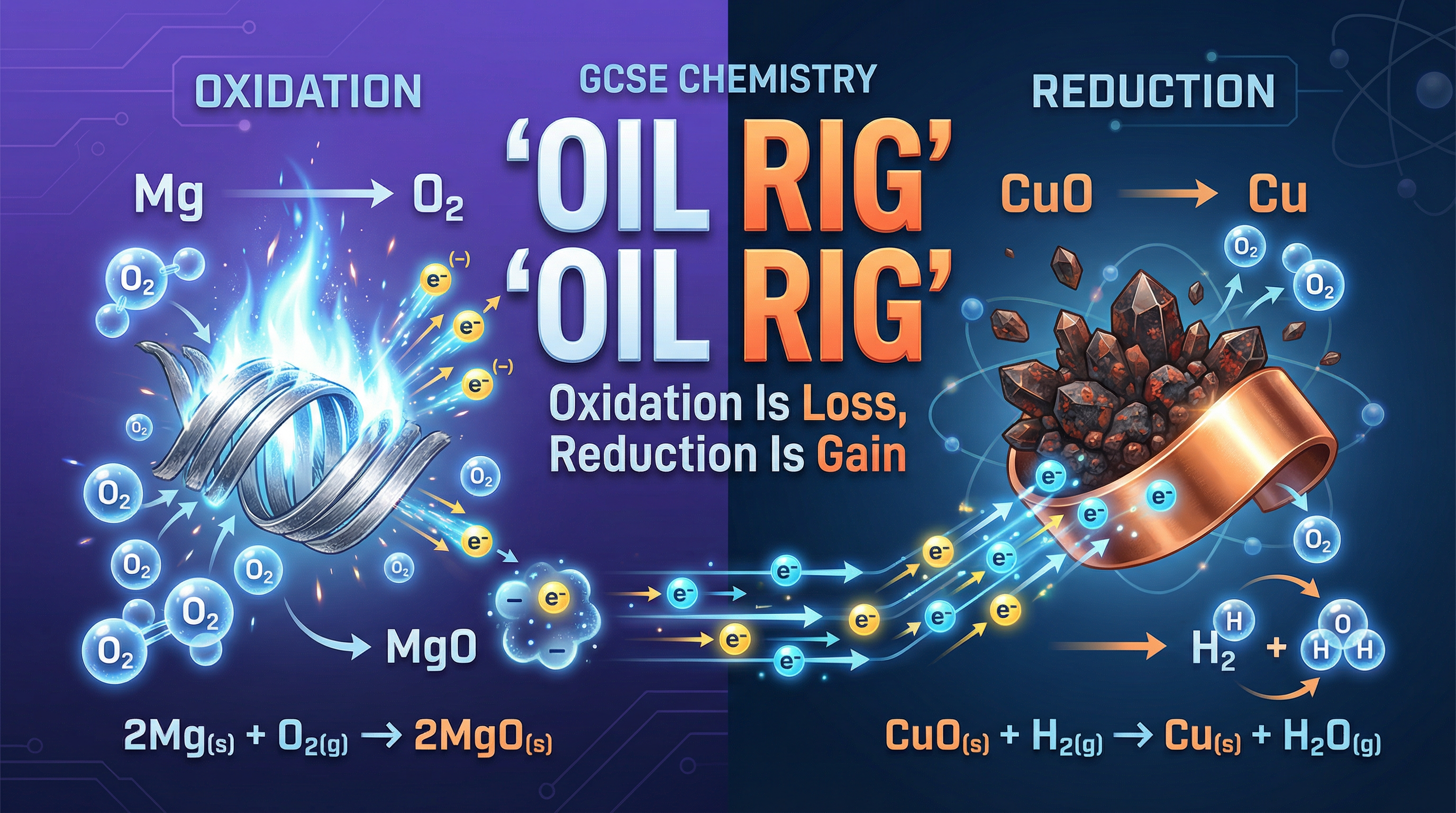

- Oxidation is Gain of Oxygen: When a substance reacts and gains oxygen atoms, it has been oxidised. A classic example is the combustion of a metal. When magnesium burns in air, it reacts with oxygen to form magnesium oxide (2Mg + O₂ → 2MgO). The magnesium has gained oxygen, so it is oxidised.

- Reduction is Loss of Oxygen: Conversely, when a substance loses oxygen atoms during a reaction, it has been reduced. This is common in the extraction of metals from their ores. For instance, copper can be extracted from copper(II) oxide by heating it with carbon (2CuO + C → 2Cu + CO₂). The copper(II) oxide has lost oxygen, so it has been reduced.

Remember: These two processes are always linked. In the copper oxide example, while the copper is reduced, the carbon gains oxygen to form carbon dioxide, so the carbon is oxidised.

Concept 2: Redox in Terms of Electrons (Higher Tier)

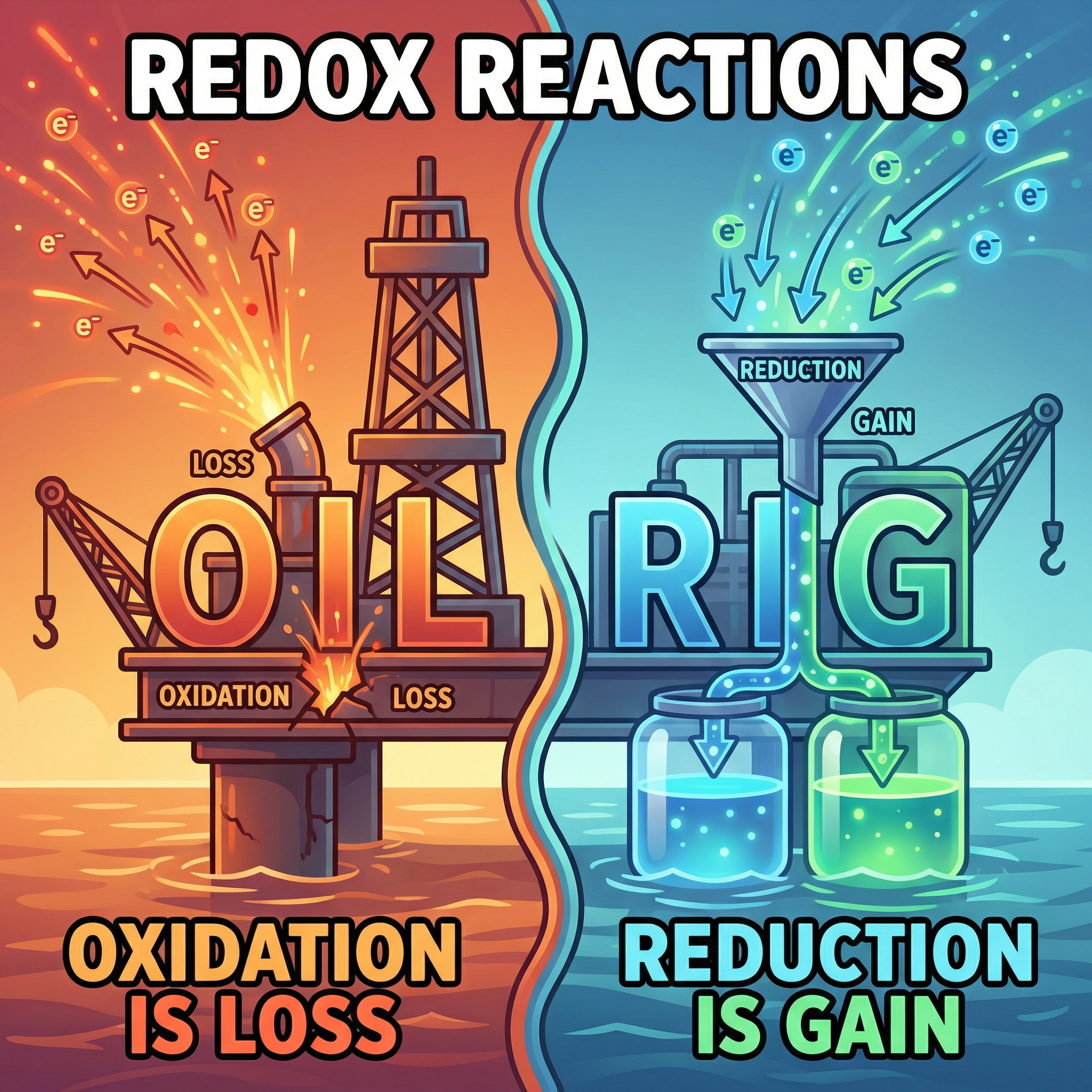

For Higher Tier candidates, a more sophisticated and versatile model is required, based on the transfer of electrons. This is where the mnemonic OIL RIG becomes your most valuable tool.

- Oxidation Is Loss (of electrons): A species is oxidised when it loses one or more electrons. When this happens, its oxidation state (a concept you'll explore more at A-Level, but for GCSE, think of it as its charge) increases. For example, a neutral sodium atom losing an electron to become a positive ion (Na → Na⁺ + e⁻) is an act of oxidation.

- Reduction Is Gain (of electrons): A species is reduced when it gains one or more electrons, causing its oxidation state/charge to decrease. For example, a chlorine molecule gaining electrons to form chloride ions (Cl₂ + 2e⁻ → 2Cl⁻) is an act of reduction.

This electron model is powerful because it applies to all redox reactions, even those where oxygen isn't involved, such as the displacement of halogens or reactions in electrolysis.

Mathematical/Scientific Relationships

Half-Equations (Higher Tier)

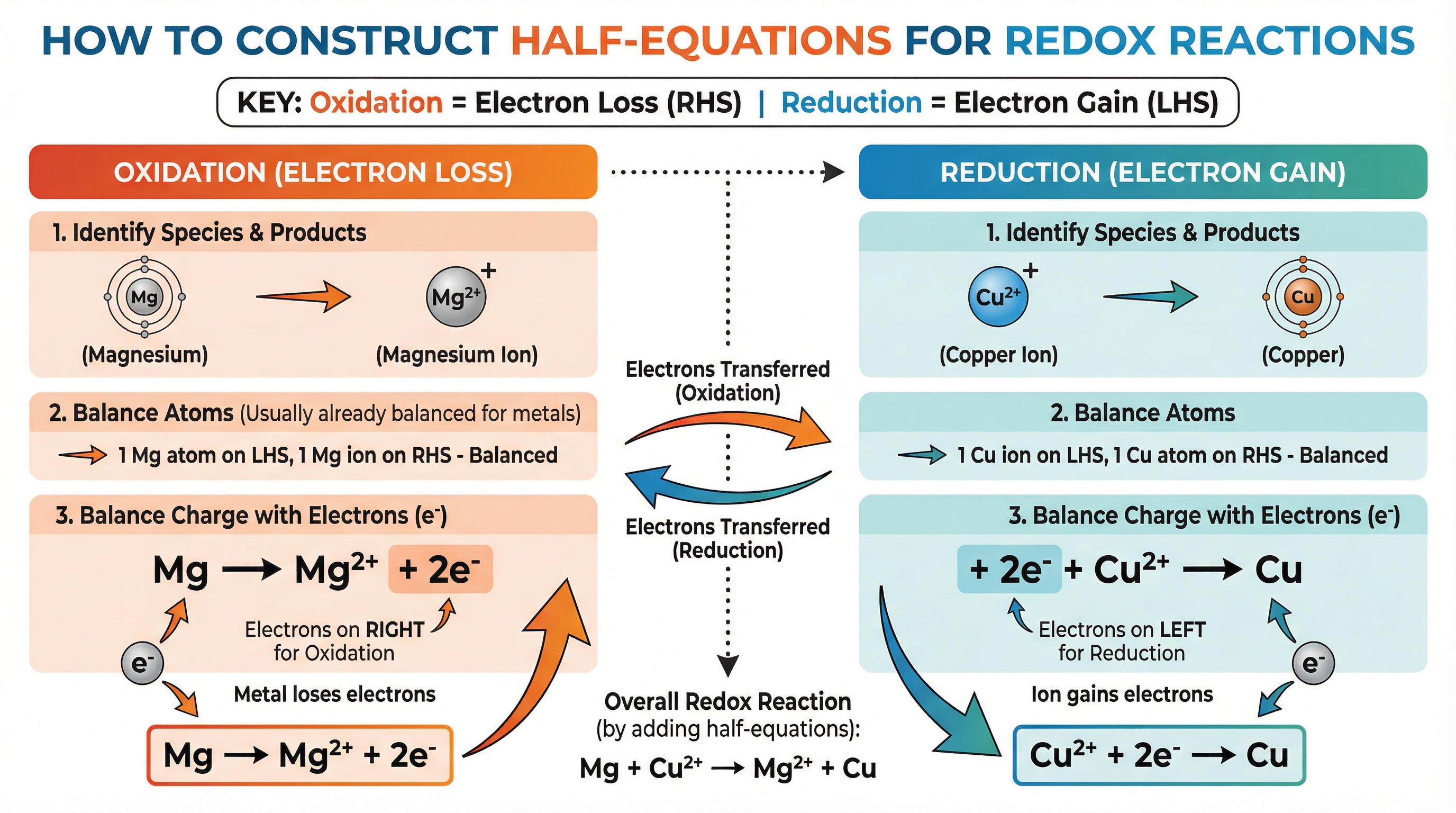

Half-equations are essential for showing exactly what happens to a single species in a redox reaction. They must be balanced for both atoms and charge, and critically, they must show the electrons (e⁻).

Rules for constructing half-equations:

- Identify the species being oxidised or reduced.

- Write the reactant on the left and the product on the right.

- Balance the atoms of the element in question.

- Balance the charge by adding electrons (e⁻) to the more positive side.

-

For Oxidation (Loss of e⁻), electrons appear on the right-hand side of the arrow.

Example: Magnesium atom oxidised to a magnesium ion

Mg → Mg²⁺ + 2e⁻ -

For Reduction (Gain of e⁻), electrons appear on the left-hand side of the arrow.

Example: Copper(II) ion reduced to a copper atom

Cu²⁺ + 2e⁻ → Cu

Combining Half-Equations

To get the full ionic equation for a redox reaction, you can combine the oxidation and reduction half-equations. The key is to ensure the number of electrons lost in the oxidation step equals the number of electrons gained in the reduction step. You may need to multiply one or both half-equations to achieve this.

Example: Reaction between Magnesium and Copper(II) ions

Oxidation: Mg → Mg²⁺ + 2e⁻

Reduction: Cu²⁺ + 2e⁻ → Cu

Since the electrons are already balanced (2e⁻ on both sides), we can simply add them together and cancel out the electrons:

Mg + Cu²⁺ → Mg²⁺ + Cu

Practical Applications

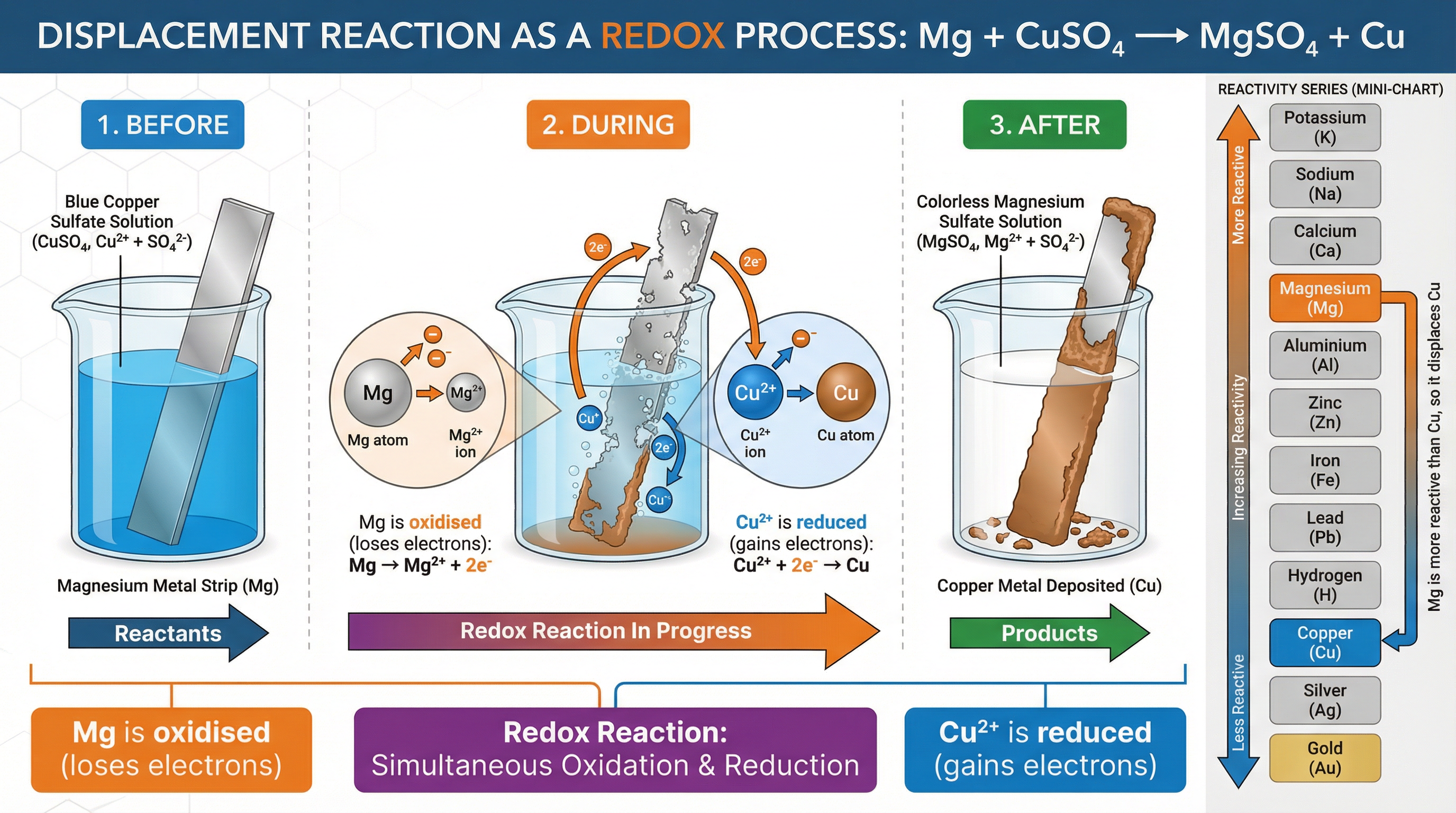

Displacement Reactions

Displacement reactions are a perfect real-world example of redox in action, directly linked to the reactivity series. A more reactive metal will displace a less reactive metal from its compound.

Example: Placing a strip of zinc metal into a beaker of blue copper(II) sulfate solution.

- Observation: The zinc strip becomes coated with a brown/pink layer of copper metal, and the blue colour of the solution fades.

- Redox Explanation: Zinc is more reactive than copper, so it has a greater tendency to lose electrons.

- Oxidation: Zinc atoms are oxidised, losing two electrons to form zinc ions:

Zn(s) → Zn²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ - Reduction: The electrons are transferred to the copper(II) ions in the solution, which are reduced to form copper atoms:

Cu²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Cu(s)

- Oxidation: Zinc atoms are oxidised, losing two electrons to form zinc ions:

- Overall Ionic Equation:

Zn(s) + Cu²⁺(aq) → Zn²⁺(aq) + Cu(s)

Sacrificial Protection

This is a practical use of displacement reactions to prevent corrosion (rusting). Iron or steel objects can be protected by attaching a block of a more reactive metal, such as zinc or magnesium. This more reactive metal is called the sacrificial anode. It corrodes (is oxidised) in preference to the iron, donating its electrons to the iron and preventing it from rusting. This is redox at work, saving bridges and ships!