Sauce making

Mastering sauce making is a gateway to understanding core food science principles for the AQA GCSE exam. This guide deconstructs the science of gelatinisation, emulsification, and reduction, providing the specific knowledge required to secure top marks by linking the functional properties of ingredients to sensory outcomes.",

"podcast_script": "SAUCE MAKING PODCAST SCRIPT - AQA GCSE Food Preparation and Nutrition

Duration: 10 minutes

Voice: Female, warm, conversational, enthusiastic educator

[INTRO - 1 minute]

Hello and welcome to your GCSE Food Preparation and Nutrition study podcast! I'm here to help you master one of the most scientifically fascinating topics on the AQA specification: sauce making.

Now, I know what you might be thinking - sauces? Really? But trust me, this topic is absolutely packed with marks-earning potential. Examiners LOVE sauce making questions because they test your understanding of the science behind cooking, not just the practical skills. And the best news? Once you understand the three key processes - gelatinisation, emulsification, and reduction - you'll be able to tackle any sauce question with confidence.

In the next ten minutes, we're going to break down the science, explore what examiners are looking for, highlight the most common mistakes students make, and finish with a quick-fire quiz to test your recall. So grab a pen, get comfortable, and let's dive into the delicious world of sauce science!

[CORE CONCEPTS - 5 minutes]

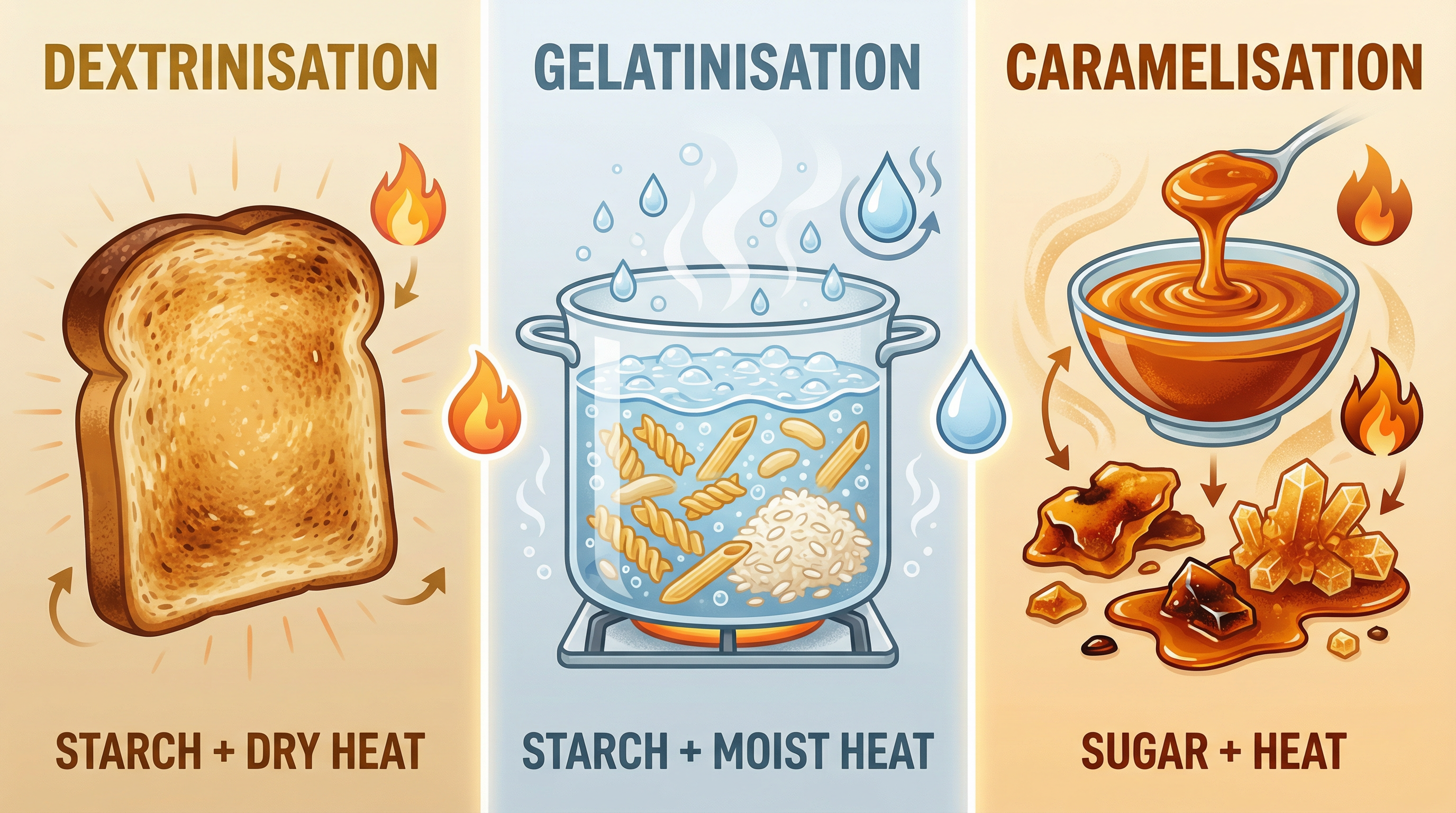

Let's start with the big one: gelatinisation. This is the process that thickens starch-based sauces like béchamel, and it's tested in almost every exam paper. Here's what you absolutely must know.

Gelatinisation is the process where starch granules absorb liquid, swell, and eventually burst to create a thick gel network. But here's the crucial detail that separates a Level 2 answer from a Level 4 answer: you need to know the TEMPERATURES at which this happens.

At 60 degrees Celsius, starch granules begin to absorb water and swell. Between 60 and 80 degrees, they continue swelling. At 80 degrees Celsius, the granules burst, releasing amylose and amylopectin molecules. And at 100 degrees - boiling point - gelatinisation is complete, and you get that smooth, thick sauce consistency.

Now, here's where students lose marks: saying "the sauce thickens because it gets hot" is NOT enough. You must explain that the starch granules swell and burst, forming a gel network. And don't forget - constant stirring is essential to prevent lumps. If you don't agitate the mixture, the starch granules stick together instead of dispersing evenly.

Let's move on to emulsification - this is all about getting oil and water to mix, which they naturally don't want to do. Think mayonnaise or hollandaise sauce. The magic ingredient here is lecithin, found in egg yolk.

Lecithin is an emulsifier. It has a hydrophilic head - that means water-loving - and a hydrophobic tail - that means oil-loving. When you whisk egg yolk with oil and an acidic liquid like lemon juice or vinegar, the lecithin molecules surround tiny oil droplets. The hydrophobic tails face inward into the oil, and the hydrophilic heads face outward into the water phase. This creates a stable emulsion.

Examiners will award marks if you can identify lecithin as the emulsifier and explain its dual nature. Don't just say "egg yolk helps them mix" - explain HOW it works at a molecular level.

Now, the third process: reduction. This is when you simmer a liquid sauce to evaporate water, which intensifies flavour and increases viscosity. The key here is understanding that as water evaporates, the concentration of flavour compounds increases, and the sauce becomes thicker because there's less liquid relative to the solids.

A common exam question asks you to explain why a reduced sauce has a stronger flavour. The answer: evaporation removes water but leaves behind the flavour molecules, so the concentration increases. Simple, but you need to use the word "concentration" or "evaporation" to get full credit.

One more thing about reduction - it's often combined with the Maillard reaction in meat-based sauces. The Maillard reaction occurs when proteins and sugars are heated together above 140 degrees Celsius, creating complex brown flavours. This is why a reduced meat jus tastes so rich and deep.

[EXAM TIPS & COMMON MISTAKES - 2 minutes]

Right, let's talk exam strategy. The AQA mark scheme rewards candidates who use precise scientific language and link functional properties to sensory outcomes. What does that mean in practice?

First, always use specific temperatures. Don't say "heat the sauce" - say "heat to 100 degrees Celsius to complete gelatinisation." This shows depth of knowledge.

Second, when describing faults in sauces, give the scientific reason. If a sauce is lumpy, don't just say "they didn't stir it." Say "the sauce is lumpy because the starch granules were not agitated during heating, causing them to clump together instead of dispersing evenly." That's a Level 4 answer.

Third, know your ratios. A standard roux uses a 1 to 1 ratio of fat to flour, and then a 1 to 10 ratio of roux to liquid. So for 50 grams of butter and 50 grams of flour, you'd add 500 millilitres of milk. This comes up in multiple-choice questions all the time.

Now, the biggest mistake students make: confusing gelatinisation with coagulation. Gelatinisation is about STARCH thickening. Coagulation is about PROTEIN setting, like when you make custard and the egg proteins set. Don't mix these up!

Another common error: saying an emulsion is stable "because you whisked it." No! It's stable because the emulsifier - lecithin - surrounds the oil droplets and prevents them from recombining. Always explain the role of the emulsifier.

And finally, for dietary adaptations: if a question asks how to make a sauce suitable for someone with coeliac disease, you need to substitute the wheat flour with a gluten-free starch like cornflour. But here's the key - you must also explain that cornflour still undergoes gelatinisation, so the functional property is maintained. That's the kind of detail that gets you into the top mark band.

[QUICK-FIRE RECALL QUIZ - 1 minute]

Okay, time to test yourself! I'll ask a question, pause for a few seconds, then give you the answer. Ready?

Question 1: At what temperature do starch granules begin to burst during gelatinisation? ... The answer is 80 degrees Celsius.

Question 2: What is the name of the emulsifier found in egg yolk? ... Lecithin.

Question 3: What is the ratio of fat to flour in a standard roux? ... 1 to 1.

Question 4: Why does a reduced sauce have a more intense flavour? ... Because water evaporates, increasing the concentration of flavour compounds.

Question 5: Name one gluten-free starch that can replace wheat flour for someone with coeliac disease. ... Cornflour, or you could also say rice flour or potato starch.

How did you do? If you got all five, brilliant! If not, go back and review those sections.

[SUMMARY & SIGN-OFF - 1 minute]

Let's wrap up. Today we've covered the three essential processes in sauce making: gelatinisation, where starch granules swell and burst at specific temperatures to thicken a sauce; emulsification, where lecithin in egg yolk allows oil and water to mix by surrounding oil droplets; and reduction, where evaporation intensifies flavour and increases viscosity.

Remember: examiners want to see scientific language, specific temperatures, and explanations that link ingredients to outcomes. Don't just describe what happens - explain WHY it happens at a molecular level.

Before your exam, make sure you can explain each process step-by-step, identify common faults and their causes, and adapt recipes for dietary needs while maintaining functional properties.

You've got this! Sauce making might seem complex, but once you understand the science, it all makes sense. Good luck with your revision, and remember - precision, explanation, and scientific terminology are your keys to top marks.

Thanks for listening, and happy studying!