Study Notes

Overview

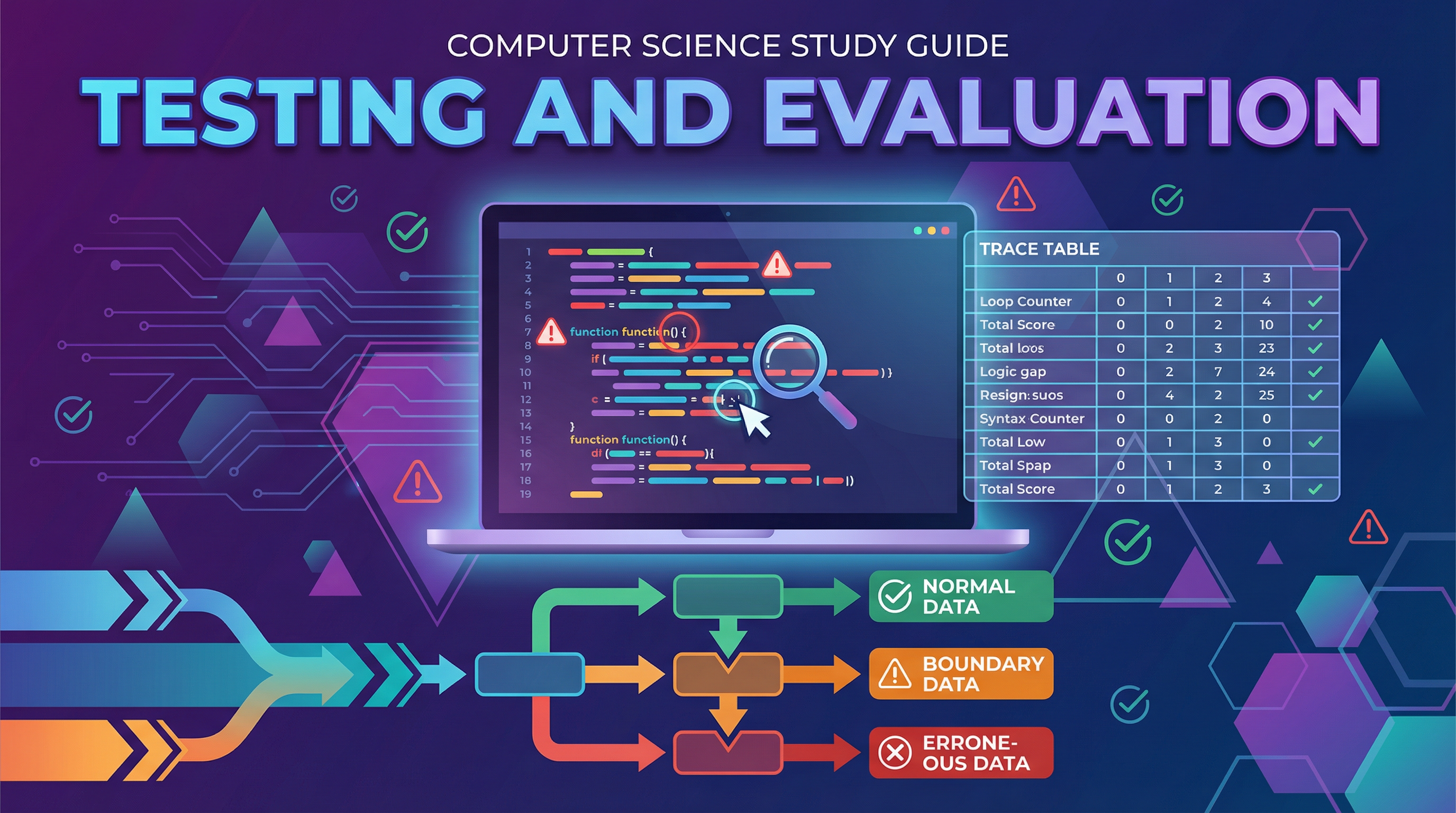

Testing and Evaluation is where Computer Science theory meets practical software development. Every application you use daily—from social media platforms to banking apps—has undergone rigorous testing to ensure it functions correctly, handles unexpected inputs gracefully, and meets user requirements. In the OCR GCSE specification, this topic assesses your understanding of how programmers systematically validate their code through test data selection, trace table execution, and error identification. You will encounter questions requiring you to select appropriate test data (Normal, Boundary, Erroneous), complete trace tables to track variable values through pseudocode execution, distinguish between syntax and logic errors, and explain the difference between iterative and final testing. Typical exam questions include providing test data with justifications (2-4 marks), completing trace tables (4-6 marks), identifying errors in code (2-3 marks), and explaining testing strategies (3-4 marks). This topic is assessed across AO1 (30%), AO2 (50%), and AO3 (20%), meaning you need both theoretical knowledge and the ability to apply it to unfamiliar scenarios.

Key Concepts

Concept 1: Types of Test Data

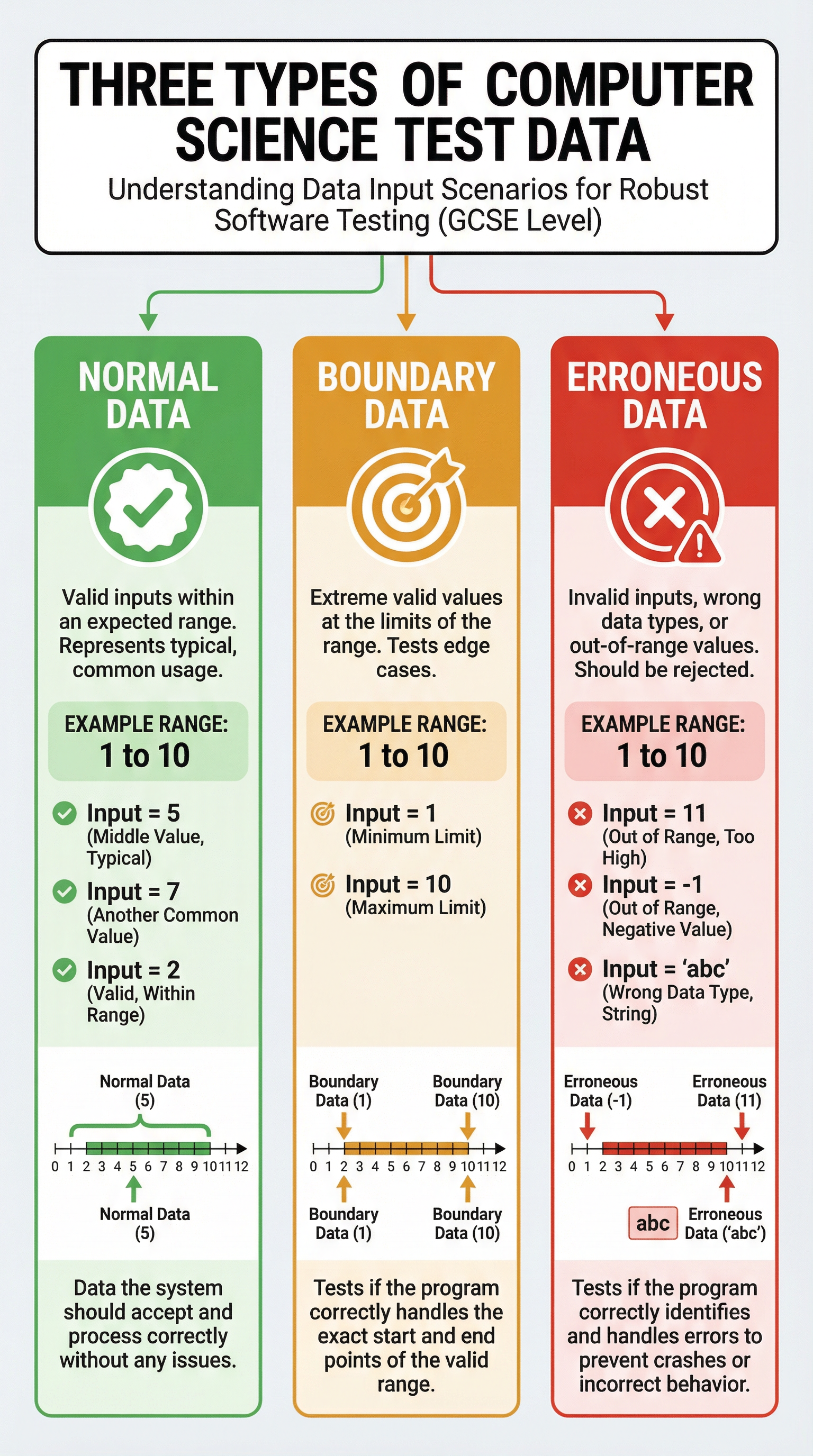

When testing a program, candidates must select test data that systematically validates different aspects of the software's behaviour. There are three distinct categories of test data, each serving a specific purpose in the testing process.

Normal Data represents typical, valid inputs that the program should accept and process correctly under standard operating conditions. For example, if a program validates ages between 1 and 100, normal data might include values such as 25, 50, or 73. Normal data confirms that the program functions correctly under everyday usage scenarios. Examiners award marks for identifying normal data that falls comfortably within the valid range and demonstrating that the program handles it without errors.

Boundary Data is the most frequently misunderstood category. Boundary data consists of values at the exact limits of the valid range—the extreme valid values that are still acceptable. This is crucial: boundary data is NOT data outside the valid range. For a range of 1 to 100, the boundary values are 1 and 100, not 0 or 101. Boundary testing is essential because errors often occur at the edges of acceptable input ranges, particularly when programmers use incorrect comparison operators (e.g., using < instead of <=). OCR examiners are extremely precise about this distinction, and candidates lose marks every year by confusing boundary data with erroneous data.

Erroneous Data (also called invalid or abnormal data) consists of inputs that the program should reject because they fall outside the valid range or are of the wrong data type. For the age example, erroneous data might include -5 (negative value), 150 (exceeds maximum), or "hello" (wrong data type). Erroneous data tests whether a program is robust—meaning it can handle unexpected or incorrect inputs gracefully without crashing, by validating inputs, displaying appropriate error messages, and continuing to function.

Example: For a program that accepts exam scores between 0 and 100:

- Normal Data: 45, 67, 82 (typical valid scores)

- Boundary Data: 0, 100 (extreme valid limits)

- Erroneous Data: -10, 150, "ninety" (invalid inputs)

Concept 2: Trace Tables

A trace table is a systematic tool used to manually simulate program execution by tracking the values of variables as each line of code is executed. Trace tables are invaluable for identifying logic errors—errors where the program runs without crashing but produces incorrect output.

When completing a trace table, candidates must work methodically through the pseudocode, updating variable values only when an assignment statement is executed. The golden rule is: do not anticipate changes. Only update a variable when the line of code that explicitly assigns a new value to that variable is reached. Many students lose marks by updating values prematurely or in the wrong row.

Trace tables typically include columns for line numbers, variable names, and output. As you step through the code, you record the current value of each variable after each assignment or modification. Conditional statements (IF, WHILE) determine which lines execute, and loops require you to trace through multiple iterations, updating values each time.

Example: Consider this pseudocode:

1 total = 0

2 counter = 1

3 WHILE counter <= 3

4 total = total + counter

5 counter = counter + 1

6 ENDWHILE

7 OUTPUT total

The trace table would be:

| Line | total | counter | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| 5 | 1 | 2 | |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| 4 | 3 | 2 | |

| 5 | 3 | 3 | |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| 4 | 6 | 3 | |

| 5 | 6 | 4 | |

| 3 | 6 | 4 | |

| 7 | 6 | 4 | 6 |

Notice how the loop condition (line 3) is checked multiple times, and values are only updated when assignment statements (lines 4 and 5) are executed.

Concept 3: Types of Errors

Programmers encounter different categories of errors during software development, and distinguishing between them is essential for effective debugging.

Syntax Errors are grammatical violations in the code that prevent the program from compiling or running. Examples include missing brackets, misspelled keywords, incorrect indentation (in Python), or using undefined variables. Syntax errors are detected by the compiler or interpreter before the program executes, and they must be fixed before the program can run. The error message typically indicates the line number and nature of the syntax violation.

Logic Errors occur when the program runs without crashing but produces incorrect or unexpected output. The code is syntactically correct, but the algorithm or logic is flawed. Examples include using the wrong comparison operator (e.g., < instead of <=), incorrect calculation formulas, or loops that iterate one too many or too few times. Logic errors are more difficult to identify because the program appears to work, but the results are wrong. Trace tables are an excellent tool for identifying logic errors by revealing where variable values deviate from expected values.

Runtime Errors occur during program execution and cause the program to crash or terminate unexpectedly. Examples include division by zero, attempting to access an array index that doesn't exist, or running out of memory. While runtime errors are not explicitly part of the OCR GCSE specification's Testing and Evaluation section, understanding them helps distinguish between errors that stop execution (syntax and runtime) and those that produce incorrect output (logic).

Example:

- Syntax Error:

IF age > 18(missing THEN keyword in pseudocode) - Logic Error:

IF age > 18 THEN OUTPUT "Adult"(should be >= 18 to include 18-year-olds) - Runtime Error:

result = 10 / 0(division by zero)

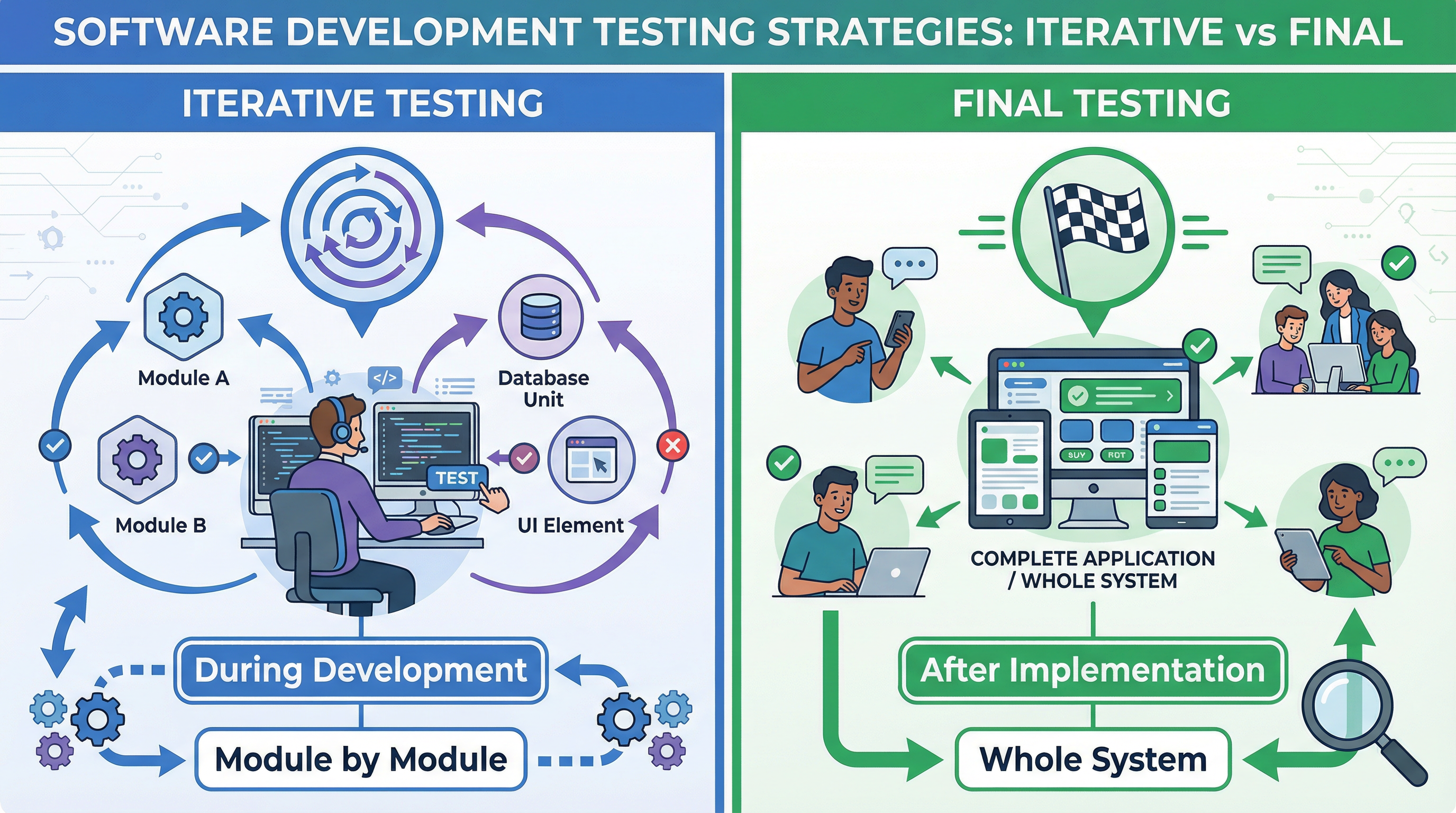

Concept 4: Iterative vs Final Testing

OCR distinguishes between two fundamental testing strategies based on when and how testing occurs during the software development lifecycle.

Iterative Testing (also called modular or unit testing) occurs during the development phase. Programmers test individual modules, subroutines, or components as they are coded, before integrating them into the complete system. Iterative testing is continuous and cyclical—code a module, test it, fix errors, code the next module, test it, and so on. This approach allows developers to identify and fix errors early, when they are easier and cheaper to correct. Iterative testing focuses on ensuring that each individual component works correctly in isolation.

Final Testing (also called system or acceptance testing) occurs after implementation, when the entire system is complete. Final testing evaluates the whole program as an integrated system, checking that all modules work together correctly, that the software meets the original requirements, and that it performs as expected in realistic usage scenarios. Final testing often involves end users or clients testing the software to ensure it meets their needs.

The key distinction for OCR exams is the timing and scope: iterative testing is "during development, module by module," while final testing is "after implementation, on the whole system." These exact phrases are essential for earning full marks.

Concept 5: Robust Programs

A robust program is one that can handle erroneous and unexpected inputs without crashing or producing nonsensical output. Robustness is achieved through input validation, error handling, and defensive programming techniques.

Input validation checks that user inputs meet specified criteria before processing them. This might include checking data types (e.g., ensuring a number is entered when expected), range checking (e.g., ensuring an age is between 0 and 120), presence checks (e.g., ensuring a required field is not empty), and format checks (e.g., ensuring an email address contains an @ symbol).

When invalid input is detected, a robust program should display a clear, user-friendly error message explaining what went wrong and what the user should do, then allow the user to re-enter the data rather than crashing or proceeding with invalid data.

Example: A robust program asking for an age might include:

REPEAT

OUTPUT "Enter your age (0-120): "

INPUT age

IF age < 0 OR age > 120 THEN

OUTPUT "Error: Age must be between 0 and 120. Please try again."

ENDIF

UNTIL age >= 0 AND age <= 120

This ensures that only valid ages are accepted, and the user receives clear feedback if their input is invalid.

Practical Applications

Testing and Evaluation principles are fundamental to all real-world software development. Professional developers use automated testing frameworks (such as JUnit for Java or pytest for Python) to systematically test their code with thousands of test cases, including normal, boundary, and erroneous data. Companies like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon employ dedicated testing teams who design comprehensive test plans, execute tests, and identify bugs before software is released to users.

In safety-critical systems—such as medical devices, aircraft control systems, and automotive software—rigorous testing is legally required and can mean the difference between life and death. The Therac-25 radiation therapy machine, for example, caused several deaths in the 1980s due to inadequate testing that failed to identify a critical logic error.

When you develop your own programs for the OCR GCSE coursework (Programming Project), you must demonstrate systematic testing by providing test plans with normal, boundary, and erroneous data, documenting expected vs actual results, and explaining how you identified and fixed errors. This practical application of Testing and Evaluation principles is worth significant marks in the coursework assessment.

Listen to the Podcast

Listen to this 10-minute podcast episode for a comprehensive audio review of Testing and Evaluation, including exam tips, common mistakes, and a quick-fire recall quiz to test your knowledge.