Study Notes

Overview

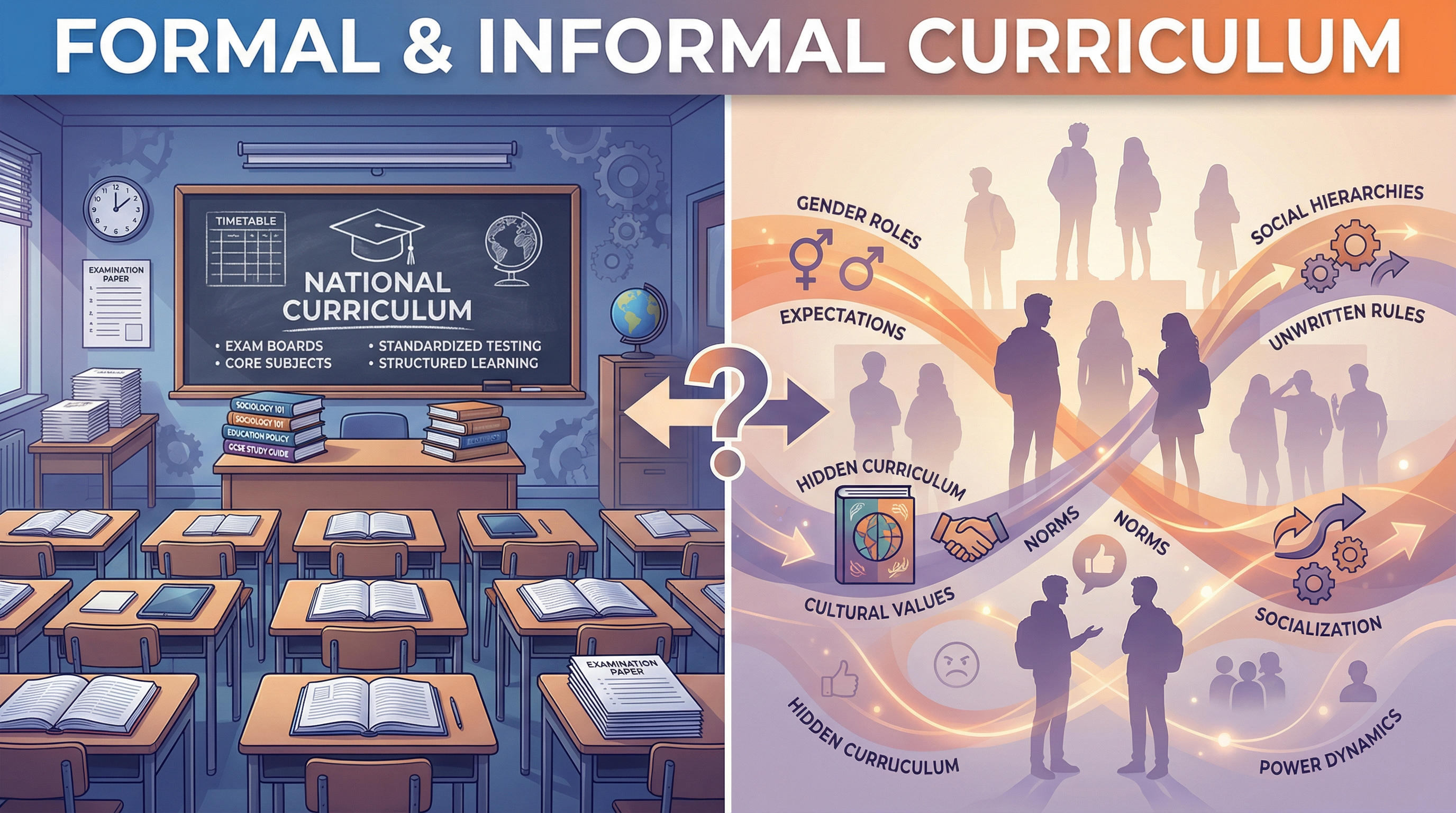

This study guide explores the critical distinction between the Formal and Informal (or Hidden) Curriculum within the British education system. The Formal Curriculum refers to the planned programme of objectives, content, learning experiences, resources, and assessment offered by a school, as exemplified by the National Curriculum established in the 1988 Education Reform Act. In contrast, the Hidden Curriculum comprises the unstated lessons, values, and perspectives that students learn implicitly. Examiners expect candidates to not only define these concepts but to critically evaluate their function and impact on different social groups. A strong response requires applying the core sociological perspectives—Functionalism, Marxism, and Feminism—to analyze how the curriculum can simultaneously be a vehicle for social mobility and a mechanism for social reproduction and control. Credit is given for demonstrating how school processes, from subject choices to classroom interactions, reinforce or challenge inequalities based on social class, gender, and ethnicity.

Key Concepts & Perspectives

The Formal Curriculum

What it is: The official, government-mandated curriculum that all state schools must follow. It includes the subjects taught, the knowledge and skills students are expected to acquire, and the methods of assessment used to measure achievement. The introduction of the National Curriculum in 1988 aimed to standardize educational provision and raise standards.

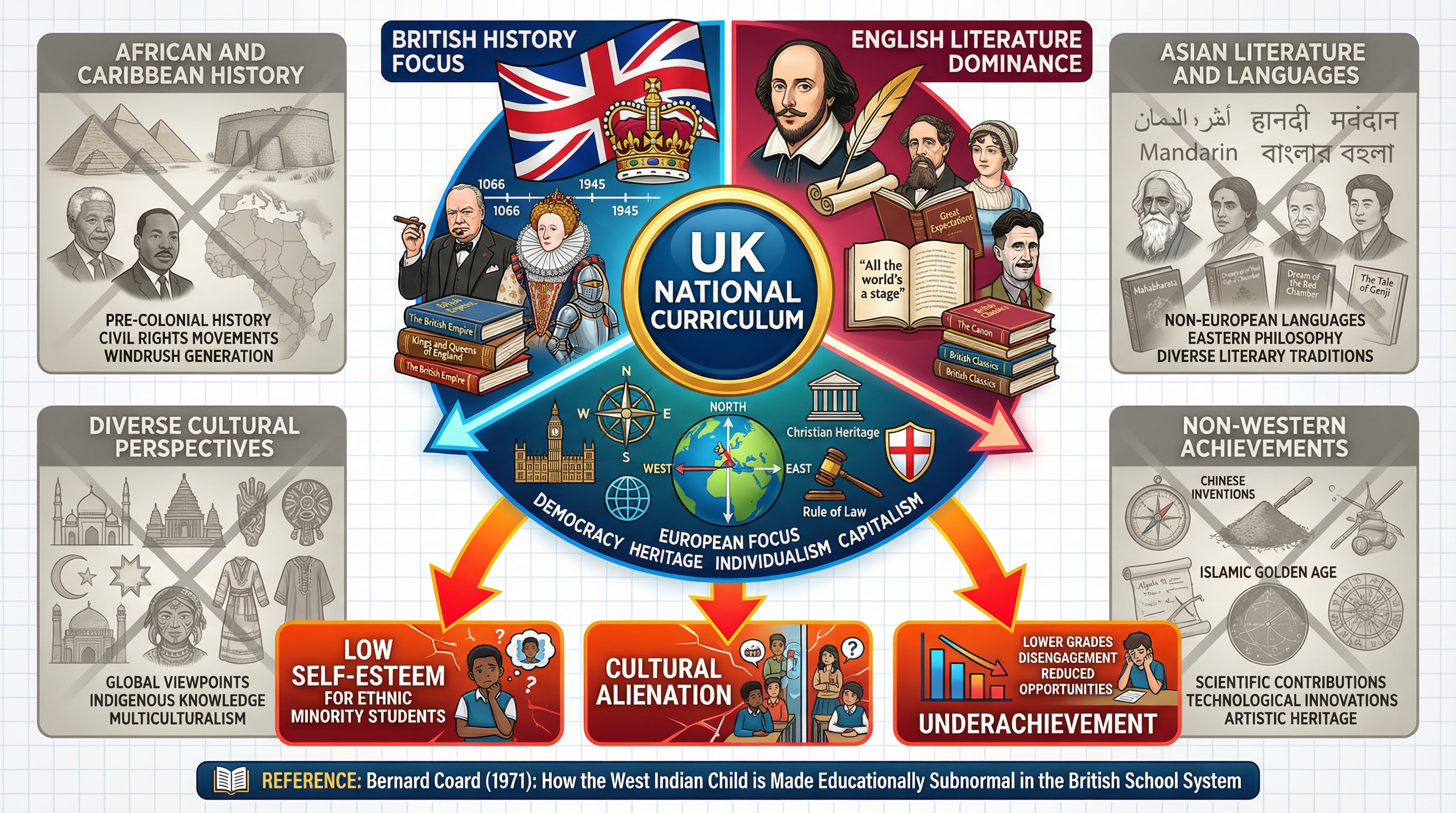

Why it matters: From a Functionalist perspective (Durkheim), the formal curriculum plays a crucial role in creating social solidarity by transmitting a shared culture and values. However, critics argue it is not neutral. For example, the concept of the Ethnocentric Curriculum suggests it prioritizes white, British culture, potentially disadvantaging ethnic minority students.

The Hidden Curriculum

What it is: The unwritten, unofficial, and often unintended lessons, values, and perspectives that students learn in school. This includes learning to deal with boredom, competing for grades, accepting hierarchy, and understanding what counts as ‘acceptable’ behaviour.

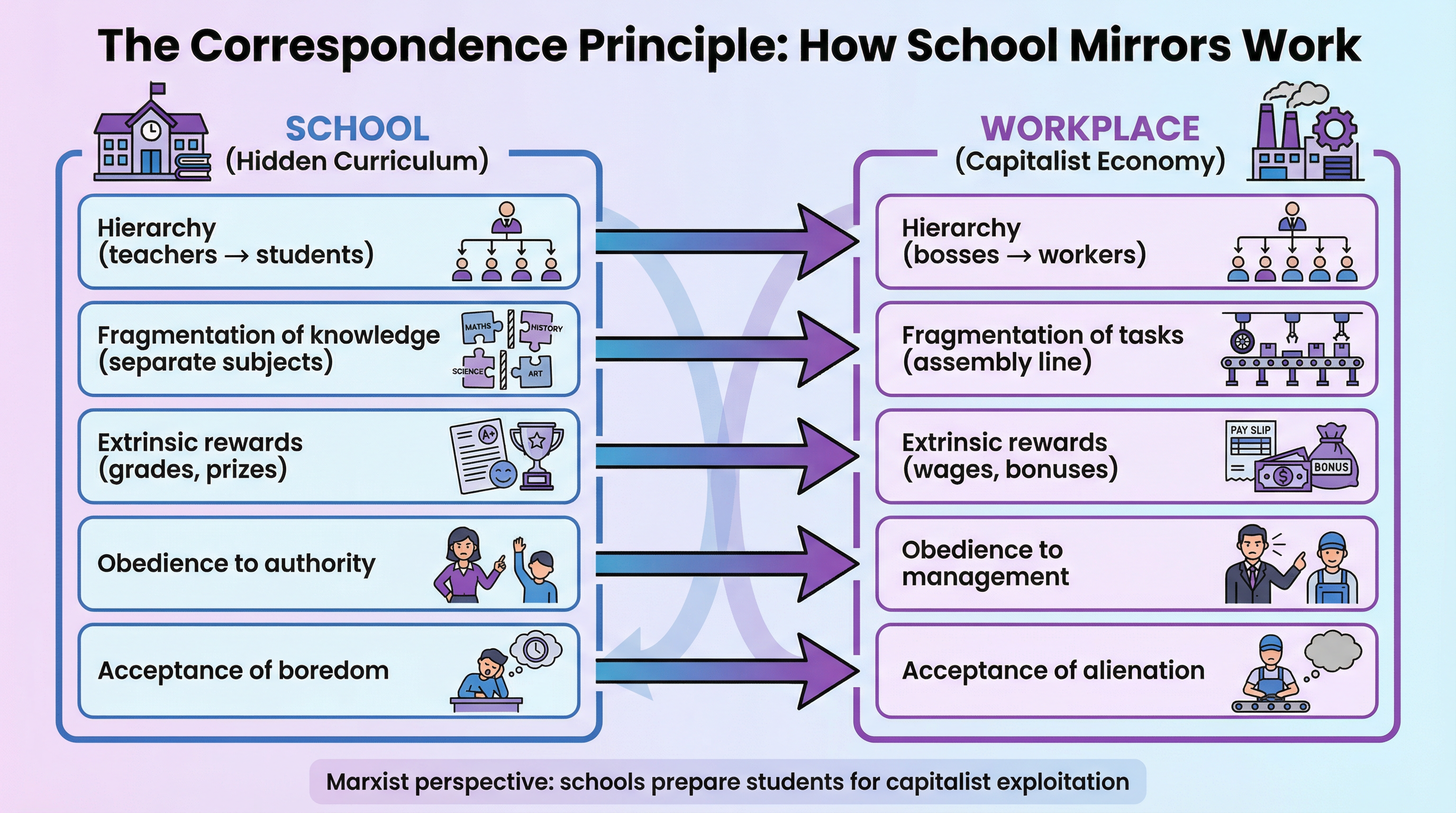

Why it matters: This is a key area of sociological debate. Marxists like Bowles and Gintis argue the hidden curriculum prepares working-class children for their future role as exploited workers through the Correspondence Principle. Feminists argue it reinforces patriarchy through gendered expectations and subject choices.

Sociological Perspectives on the Curriculum

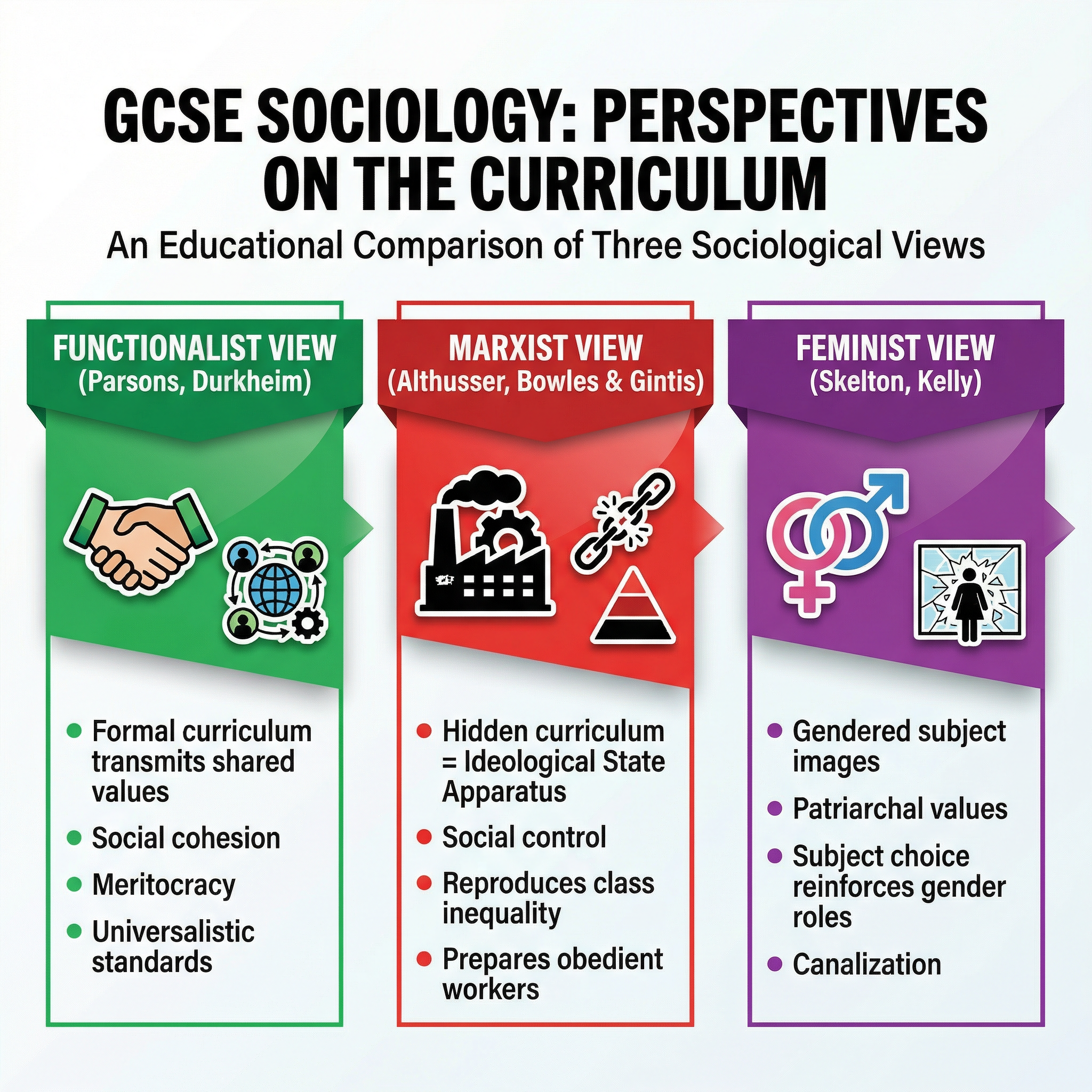

Functionalist View

Key Theorists: Émile Durkheim, Talcott Parsons

Core Idea: The curriculum is a vital mechanism for integrating individuals into society. It teaches the specialized skills needed for a complex division of labour and transmits universalistic values, ensuring that everyone is judged by the same standards (meritocracy). The hidden curriculum helps children transition from the particularistic values of the family to the universalistic values of wider society.

Marxist View

Key Theorists: Louis Althusser, Samuel Bowles & Herbert Gintis

Core Idea: The curriculum is an Ideological State Apparatus (Althusser) that serves the interests of the ruling class. The hidden curriculum, through the Correspondence Principle, creates a subservient, docile workforce by mirroring the features of capitalist employment (hierarchy, fragmentation, extrinsic rewards). It legitimizes inequality by creating a ‘myth of meritocracy’.

Feminist View

Key Theorists: Ann Oakley, Sue Sharpe, Christine Skelton, Alison Kelly

Core Idea: The curriculum perpetuates gender inequality. This occurs through various processes:

- Gendered Subject Images: Subjects are often seen as ‘masculine’ (e.g., Physics, IT) or ‘feminine’ (e.g., Sociology, English), influencing student choices.

- Canalization: Teachers and peers may steer students towards subjects deemed appropriate for their gender.

- Patriarchal Values: The content of subjects (e.g., history focusing on male figures) and the structure of schools can reinforce traditional gender roles.