Study Notes

Overview

The digital divide is a term used to describe the gap between those who have ready access to computers and the internet, and those who do not. For AQA GCSE Sociology, you must understand this not just as a technical issue, but as a profound form of social inequality. This guide covers the key dimensions of the digital divide, focusing on how factors like social class, age, gender, and global location create significant disparities in life chances. Examiners expect candidates to distinguish between mere access to technology and the crucial skills required for its effective usage. We will explore the real-world consequences of this divide, such as the 'homework gap' in education and barriers to employment, and analyse it through the lens of sociological theories like Marxism and Functionalism. This topic is vital for understanding contemporary social stratification and requires you to apply sociological concepts to the rapidly changing digital landscape.

Key Concepts & Dimensions

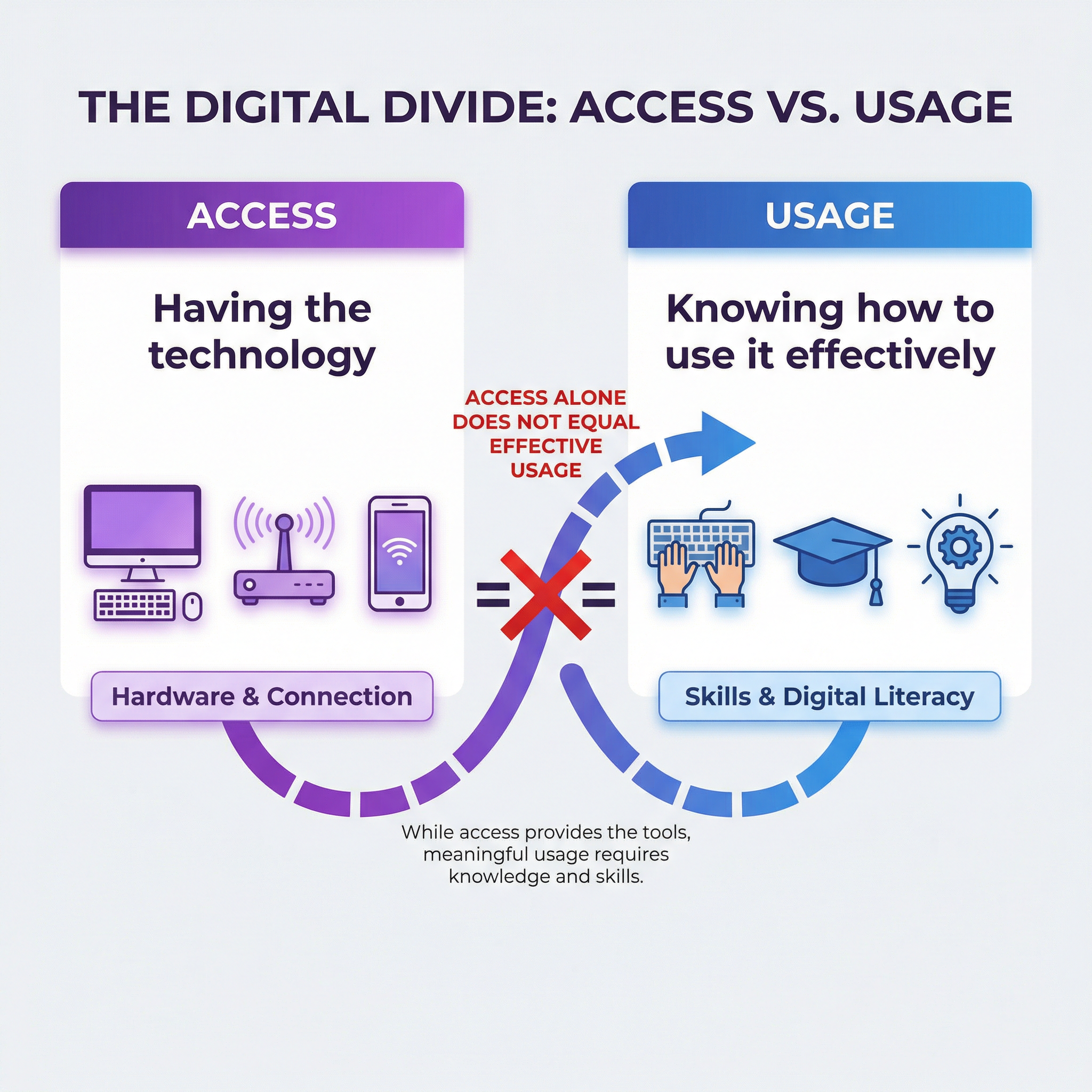

The Access vs. Usage Gap

What it is: This is a fundamental distinction that examiners want to see. It is not enough to simply have a laptop or a phone; the digital divide is also about what you can do with it.

- Access: Refers to the physical ownership of hardware (e.g., laptops, smartphones) and a reliable internet connection (e.g., broadband). Material deprivation is a key barrier to access.

- Usage: Refers to the skills, knowledge, and confidence to use technology effectively. This includes digital literacy – the ability to find, evaluate, and create information using digital platforms. Cultural capital, such as having parents who can model effective internet use, plays a significant role here.

Why it matters: Candidates who only discuss access will lose marks. The most insightful analysis comes from explaining how a lack of skills (the usage gap) can be just as damaging as a lack of hardware. For example, an elderly person may have a tablet but be unable to use it for online banking, leaving them financially excluded.

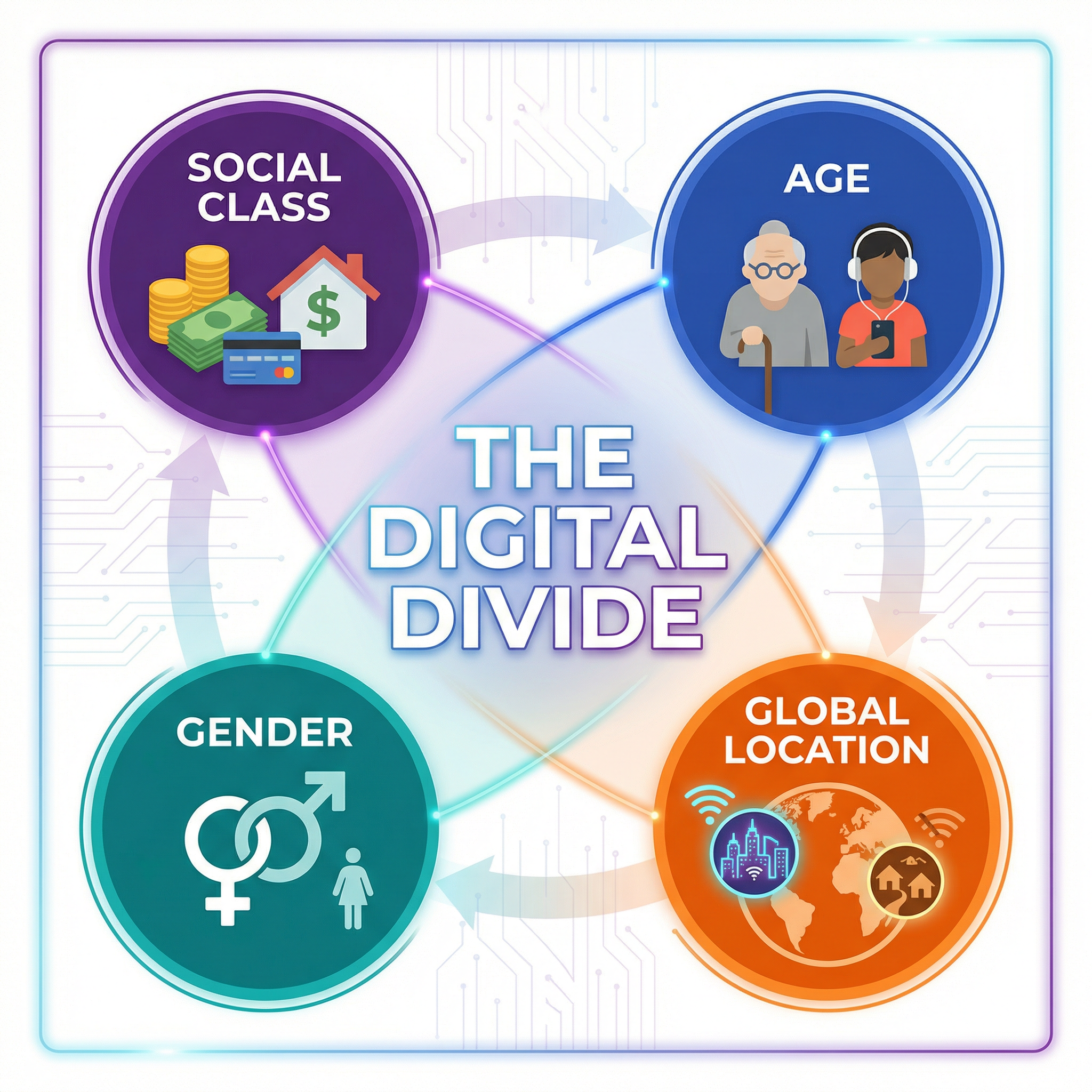

Dimensions of the Digital Divide

What it is: The divide doesn't affect everyone equally. It intersects with other forms of social inequality.

- Social Class: This is arguably the most significant factor. Higher-income households are more likely to afford multiple devices, high-speed internet, and the latest software. Sociologist Ellen Helsper (2011) found that middle-class individuals are more likely to use the internet to build 'digital capital' – using it for job searching, networking, and financial management. In contrast, working-class users may engage in more passive, entertainment-focused activities.

- Age: There is a clear 'generational divide'. Younger people, often termed 'digital natives', have grown up with technology and integrate it into all aspects of their lives. Older people may be 'digital tourists', lacking confidence and facing a steeper learning curve. According to Ofcom's 2020 report, older adults are the group most likely to be entirely offline.

- Global Location: The 'global digital divide' refers to the vast inequality in internet penetration between developed nations (e.g., UK, USA) and developing countries. This limits the ability of poorer nations to participate in the global economy and access information, reinforcing global inequality.

- Gender: In the UK, the gender gap in basic internet access has largely closed. However, differences in usage persist. Some research suggests men are more likely to engage in complex digital activities and are more confident in their skills, while women may use technology more for social communication.

Why it matters: In exam answers, you must be specific about which groups are affected and how. Linking these dimensions together (e.g., discussing the challenges faced by an elderly, working-class woman) demonstrates a sophisticated understanding.

Second-Order Concepts

Causation

- Economic Factors: The primary cause is material deprivation. The cost of hardware, broadband subscriptions, and data plans is a significant barrier for low-income families.

- Social Factors: A lack of cultural capital is crucial. Children from professional backgrounds are more likely to have parents who can teach them how to use technology for educational and professional gain.

- Geographical Factors: Urban areas typically have better and cheaper internet infrastructure than rural areas, creating a 'postcode lottery' of connectivity.

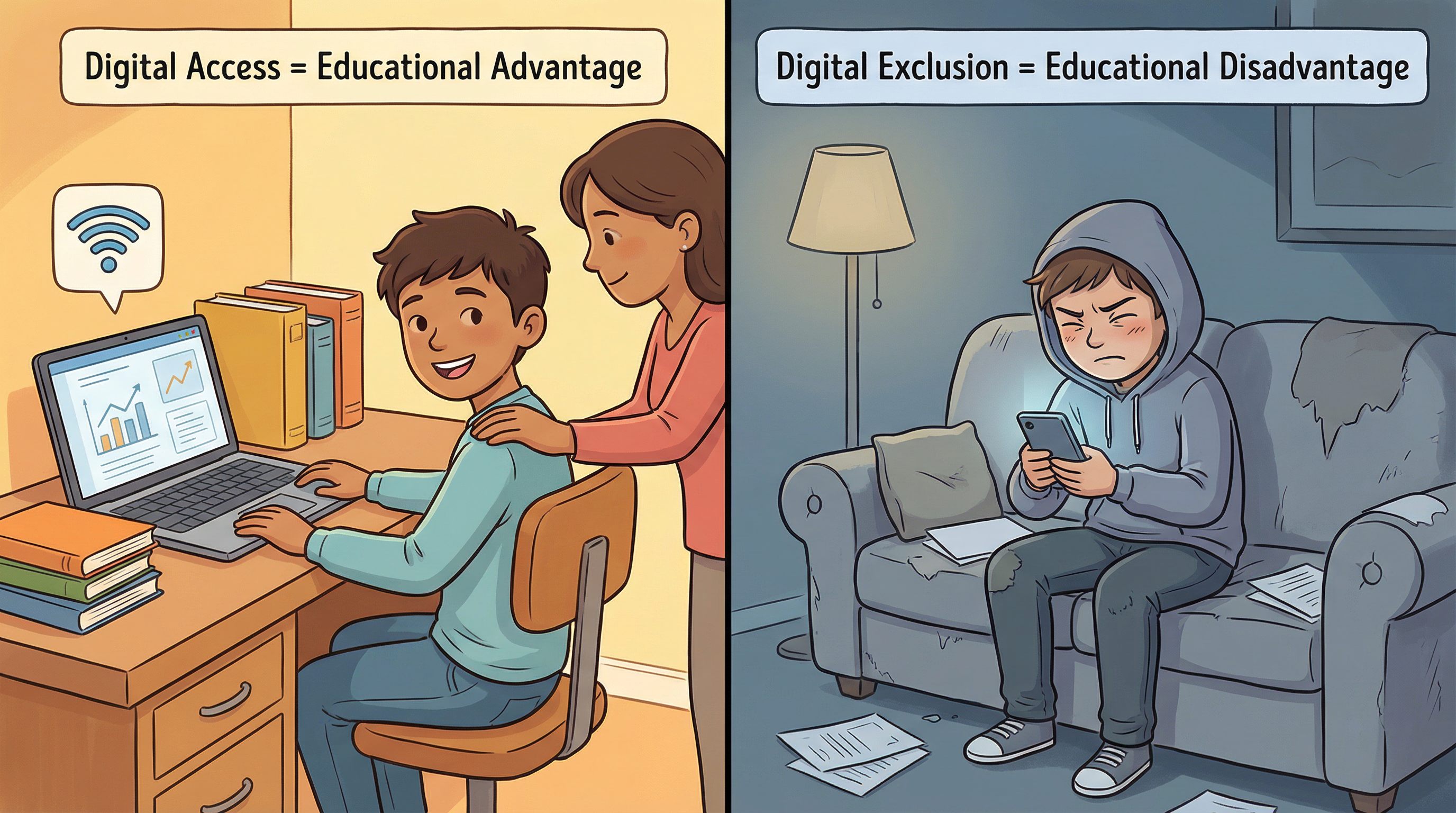

Consequence

- Educational Underachievement: The 'homework gap' is a major consequence. Students without reliable internet access struggle to complete research, submit assignments, or access online learning platforms. This was starkly highlighted during the school closures of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Employment Barriers: Many jobs now require online applications and a high level of digital literacy. The 'digital underclass' is therefore excluded from large parts of the job market, limiting their social mobility.

- Social Exclusion: Everyday activities, from banking and shopping to accessing government services, are moving online. Those without digital skills can become socially and financially isolated.

Theoretical Perspectives

Marxism

Marxists view the digital divide as a new form of class inequality that benefits the bourgeoisie (the ruling class). The wealthy can afford the technology and training to give themselves and their children a competitive advantage, while the proletariat (the working class) is left further behind. The internet, rather than being a democratising force, becomes another tool for reproducing class inequality. The digital underclass is a modern manifestation of the reserve army of labour.

Functionalism

Functionalists might see the digital divide as a temporary dysfunction or 'lag' in society. They would argue that as technology becomes cheaper and more integrated, the divide will naturally shrink. From this perspective, learning digital skills is part of the value consensus – a necessary function for maintaining social order and economic prosperity in a modern society. The divide represents a failure of socialisation for some groups, which can be fixed through education and training initiatives.