Study Notes

Overview

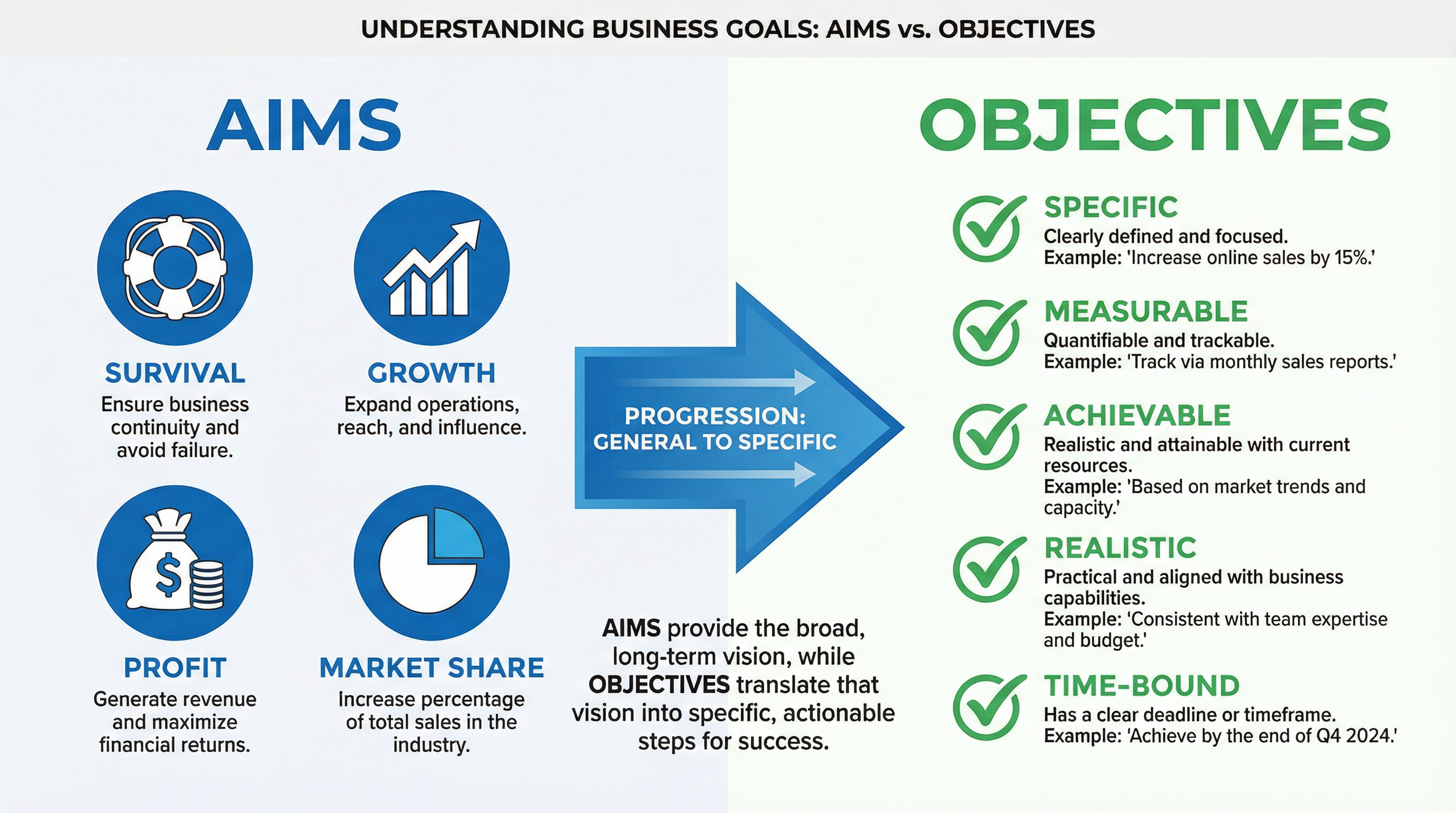

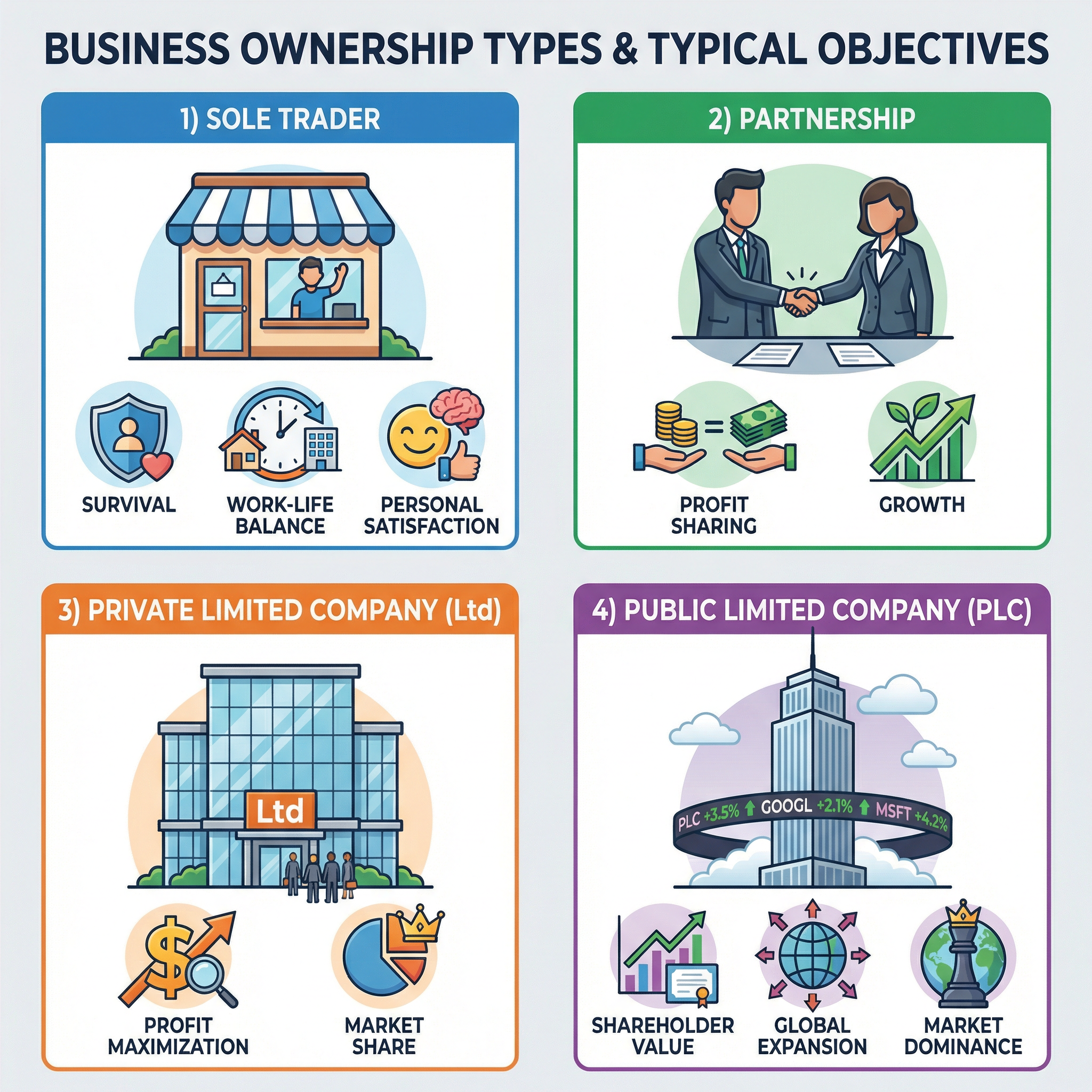

Setting business aims and objectives forms the strategic backbone of every successful enterprise, from sole traders operating local shops to multinational PLCs competing on global markets. This topic requires candidates to distinguish clearly between broad aims (long-term, general goals such as survival, profit, growth, and market share) and specific objectives (measurable, time-bound targets that operationalize those aims). The OCR GCSE Business specification emphasizes the application of SMART criteria (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-bound) to evaluate whether proposed objectives are fit for purpose. Examiners expect candidates to demonstrate contextual awareness by matching objectives to business ownership structures, recognizing that a sole trader prioritizing work-life balance faces fundamentally different pressures than a PLC accountable to shareholders demanding quarterly returns. Assessment focuses on three core skills: defining and distinguishing aims from objectives, applying SMART criteria to real-world scenarios, and analyzing conflicts between financial objectives (profit maximization, sales revenue growth) and non-financial objectives (ethical sourcing, environmental sustainability, employee welfare). Candidates must develop chains of reasoning using the BLT structure (Because, Leading to, Therefore) to explain how specific objectives drive business outcomes, and they must root every answer in case study context by referencing business names, owner circumstances, market conditions, and financial data. This topic accounts for significant AO1 (knowledge), AO2 (application), and AO3 (analysis) marks across multiple question types, making it essential foundational knowledge for the entire specification.

Key Concepts & Definitions

Aims vs. Objectives

The distinction between aims and objectives is fundamental and frequently tested. Aims are broad, qualitative, long-term goals that provide overall direction for the business. They answer the question "What do we want to achieve in general?" Common business aims include survival (especially for start-ups and businesses facing economic downturns), profit (generating revenue exceeding costs), growth (expanding operations, market reach, or product lines), and market share (increasing the percentage of total industry sales). For example, a newly opened independent bookshop might have the aim of "survival" for its first two years, while an established supermarket chain like Tesco might have the aim of "growth" through geographic expansion or diversification into new product categories. Objectives, by contrast, are specific, quantifiable, short-to-medium-term targets that translate aims into actionable steps. They answer the question "Exactly what will we achieve, by when, and how will we measure success?" An objective must meet SMART criteria to be effective. For instance, transforming the vague aim of "profit" into the objective "increase net profit margin from 8% to 12% within 18 months by renegotiating supplier contracts and reducing waste by 15%" provides clear direction, accountability, and measurability. Examiners penalize candidates who confuse these terms or provide aims when objectives are requested, so precision in language is critical.

SMART Objectives

The SMART framework is the gold standard for setting effective business objectives, and candidates must be able to apply each criterion to case study scenarios. Specific means the objective is clearly defined and focused, leaving no ambiguity about what is to be achieved. For example, "improve customer satisfaction" is too vague, whereas "increase average customer satisfaction score from 7.2 to 8.5 out of 10 on post-purchase surveys" is specific. Measurable means the objective includes quantifiable metrics that allow progress to be tracked and success to be verified. Metrics might include percentages, currency amounts, units sold, or customer ratings. Achievable means the objective is realistic given the business's current resources, capabilities, and market conditions. Setting an objective to "double market share within six months" might be achievable for a disruptive tech start-up with venture capital backing, but wholly unrealistic for a mature business in a saturated market. Realistic (sometimes called Relevant) means the objective aligns with the business's broader aims, values, and strategic priorities. For example, an objective to "expand into luxury goods" would be unrealistic for a discount retailer whose brand identity and customer base are built on affordability. Time-bound means the objective specifies a clear deadline or timeframe for achievement, creating urgency and enabling performance review. "Increase online sales by 20%" lacks a time dimension; "increase online sales by 20% by the end of Q4 2026" is time-bound. Examiners frequently ask candidates to evaluate whether a proposed objective is SMART, or to rewrite a weak objective to meet SMART criteria, so this framework must be thoroughly internalized.

Financial vs. Non-Financial Objectives

Businesses pursue both financial and non-financial objectives, and understanding the distinction and potential conflicts between them is essential for higher-level analysis. Financial objectives are quantifiable targets related to monetary performance and shareholder value. Common financial objectives include profit maximization (achieving the highest possible profit margin), sales revenue growth (increasing total income from sales), return on investment (ROI, measuring profit relative to capital invested), market share increase (capturing a larger percentage of total industry sales), and cost reduction (lowering operational expenses to improve margins). For example, a PLC might set the financial objective of "achieving a 15% return on equity (ROE) to satisfy shareholder expectations and maintain share price." Non-financial objectives relate to qualitative goals that may not directly generate profit but contribute to long-term sustainability, reputation, and stakeholder satisfaction. These include social responsibility (ethical sourcing, fair wages, community investment), environmental sustainability (reducing carbon footprint, minimizing waste, using renewable energy), customer satisfaction (improving service quality, building loyalty), employee welfare (providing training, ensuring workplace safety, promoting work-life balance), and personal satisfaction (particularly relevant for sole traders who value autonomy and fulfillment over maximum profit). For example, a sole trader running an organic café might prioritize the non-financial objective of "sourcing 100% of ingredients from local, ethical suppliers within 50 miles" even if this increases costs and reduces profit margins. Examiners reward candidates who recognize that financial and non-financial objectives often conflict, requiring businesses to make trade-offs. A business seeking to maximize profit might be tempted to use cheaper, unethical suppliers, conflicting with social responsibility objectives. A sole trader aiming for rapid growth might sacrifice work-life balance, leading to burnout. High-scoring answers analyze these tensions and evaluate which objective should take priority given the specific business context.

Business Ownership Types and Typical Objectives

Different business ownership structures face distinct pressures, constraints, and stakeholder expectations, leading them to prioritize different objectives. Understanding this relationship is critical for applying knowledge to case study contexts.

Sole Traders

Sole traders are individuals who own and run their businesses independently, retaining all profits but bearing unlimited personal liability for debts. This ownership structure profoundly shapes their objectives. Survival is often the primary objective, especially in the first two years when cash flow is unpredictable and competition is intense. A sole trader operating a local hairdressing salon might set the objective of "covering all fixed costs and achieving break-even within the first 12 months." Work-life balance is another common priority, as sole traders often start businesses to escape the rigid structures of employment and gain control over their time. An objective might be "limiting working hours to 40 per week while maintaining monthly revenue of £4,000." Personal satisfaction and autonomy are significant motivators; many sole traders value the ability to make independent decisions and pursue their passions, even if this means sacrificing higher profits. For example, a sole trader running a vintage bookshop might prioritize curating a unique, high-quality collection over stocking bestsellers that would generate more revenue. Financial objectives such as profit maximization are often secondary to these non-financial goals, particularly in the early stages. However, as the business stabilizes, sole traders may shift focus toward growth or profit objectives to reinvest in equipment, hire staff, or expand premises.

Partnerships

Partnerships involve two or more individuals sharing ownership, decision-making, profits, and liabilities. This structure introduces the need for aligned objectives among partners, which can be both a strength and a source of conflict. Profit sharing is a central objective, as partners typically agree on a formula for distributing profits based on capital contributions, effort, or other criteria. An objective might be "achieving a net profit of £120,000 annually, distributed 60-40 between partners based on initial investment." Growth is often prioritized more than in sole trader businesses, as partnerships have greater combined resources, skills, and networks to support expansion. For example, a partnership of two architects might set the objective of "securing three new commercial contracts worth a combined £500,000 within 18 months." Partnerships may also focus on specialization, with each partner contributing distinct expertise, leading to objectives such as "increasing efficiency by 20% through division of labor, with Partner A focusing on client acquisition and Partner B on project delivery." However, partnerships face the challenge of conflicting personal objectives; one partner might prioritize aggressive growth while another values stability and work-life balance. Effective partnerships establish clear, mutually agreed objectives in partnership agreements to avoid disputes.

Private Limited Companies (Ltd)

Private limited companies are incorporated businesses with limited liability, meaning shareholders' personal assets are protected if the business fails. Shares are privately held and cannot be traded on public stock exchanges. This structure allows for greater capital raising than sole traders or partnerships, leading to more ambitious objectives. Profit maximization becomes a stronger priority, as shareholders expect returns on their investment, though the pressure is less intense than in PLCs. An objective might be "increasing profit after tax by 18% year-on-year to fund dividend payments and reinvestment in R&D." Market share growth is often pursued to strengthen competitive positioning and achieve economies of scale. For example, a private limited company operating a regional chain of gyms might set the objective of "capturing 25% of the local fitness market within three years by opening five new locations." Retention of control is a key consideration; private limited companies often resist going public to avoid external shareholder pressure and maintain strategic autonomy. Objectives might include "achieving sustainable growth of 10-15% annually without requiring external equity investment." Non-financial objectives such as corporate social responsibility and employee development are increasingly prioritized by private limited companies seeking to build strong employer brands and customer loyalty, particularly in competitive industries.

Public Limited Companies (PLCs)

Public limited companies are incorporated businesses whose shares are traded on public stock exchanges, making them accessible to a wide range of investors. This ownership structure creates intense pressure to deliver short-term financial performance to satisfy shareholders and maintain share prices. Shareholder value is the dominant objective, typically measured through metrics such as earnings per share (EPS), return on equity (ROE), and dividend yield. An objective might be "achieving a 12% annual increase in EPS to meet analyst expectations and prevent share price decline." Market dominance and global expansion are common objectives for large PLCs seeking to leverage economies of scale and access new revenue streams. For example, a multinational PLC in the retail sector might set the objective of "entering five new international markets within 24 months, targeting combined revenue of £200 million." Quarterly profit targets drive decision-making, as PLCs must report financial results every three months, creating pressure to prioritize short-term gains over long-term sustainability. This can lead to conflicts with non-financial objectives such as environmental sustainability or employee welfare, as cost-cutting measures to boost quarterly profits might involve reducing staff training budgets or delaying investments in green technology. However, leading PLCs increasingly recognize that strong environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance enhances reputation, attracts ethical investors, and mitigates regulatory risks, leading to objectives such as "achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2040" or "ensuring 100% supply chain transparency by 2028." Examiners expect candidates to recognize these tensions and evaluate trade-offs in context.

Conflicts Between Objectives

Businesses frequently face situations where pursuing one objective undermines another, requiring difficult trade-offs. Analyzing these conflicts is a hallmark of high-level AO3 responses. One common conflict is between profit maximization and ethical sourcing. A clothing retailer might maximize profit by sourcing garments from low-cost factories with poor labor standards, but this conflicts with social responsibility objectives and risks reputational damage if exposed. Conversely, committing to ethical sourcing increases costs, reducing profit margins. A balanced approach might involve setting the objective of "sourcing 50% of products from certified ethical suppliers within two years, while maintaining a minimum net profit margin of 8%." Another frequent conflict is between growth and work-life balance, particularly for sole traders and small business owners. Rapid expansion requires long hours, significant stress, and personal sacrifice, undermining the work-life balance that motivated many entrepreneurs to start their businesses. A sole trader might set the objective of "limiting growth to 10% annually to preserve personal well-being and family time." Short-term profit vs. long-term sustainability is a critical tension for PLCs under pressure to deliver quarterly results. Investing in research and development, employee training, or environmental initiatives reduces short-term profits but strengthens long-term competitiveness and resilience. A PLC might set the objective of "allocating 5% of annual revenue to R&D despite short-term profit impact, targeting a 20% increase in innovative product launches within three years." Market share growth vs. profit margins can also conflict; aggressive pricing strategies to capture market share reduce profit per unit sold, while premium pricing protects margins but limits volume. A business might set the objective of "accepting a 3% reduction in profit margin for 18 months to achieve a 10% increase in market share, then raising prices once customer loyalty is established." Examiners reward candidates who identify these conflicts, explain the trade-offs using chains of reasoning, and recommend a balanced approach tailored to the specific business context.

How Objectives Evolve Over Time

Business objectives are not static; they evolve in response to internal changes (such as growth, profitability, or leadership transitions) and external influences (such as economic conditions, technological disruption, or regulatory changes). Understanding this dynamic is essential for contextual application. In the start-up phase, survival is typically the overriding objective. A new business might set the objective of "achieving positive cash flow within six months to avoid insolvency." Once survival is secured, the focus shifts to growth, with objectives such as "increasing customer base by 50% within 12 months through targeted social media advertising." As the business matures and growth stabilizes, profit maximization becomes a priority, with objectives such as "improving net profit margin from 10% to 15% by streamlining operations and renegotiating supplier contracts." In the maturity phase, businesses may pursue diversification to reduce reliance on a single product or market, setting objectives such as "launching two new product lines within 18 months to capture adjacent market segments." If the business faces decline due to market saturation or technological obsolescence, objectives might shift to cost reduction and restructuring, such as "reducing operational costs by 20% through automation and workforce optimization." External factors also drive objective changes. During an economic recession, businesses might shift from growth to survival objectives, prioritizing cash flow and cost control. Conversely, during an economic boom, businesses might pursue aggressive expansion objectives. Regulatory changes can force businesses to adopt new objectives; for example, the introduction of stricter environmental regulations might lead a manufacturing business to set the objective of "reducing carbon emissions by 30% within five years through investment in renewable energy and process optimization." Examiners reward candidates who recognize that objectives must be flexible and responsive to changing circumstances, and who can recommend appropriate objective shifts based on case study data.

Applying Objectives to Case Study Contexts

OCR GCSE Business exams are heavily context-dependent, meaning candidates must apply their knowledge to specific business scenarios rather than providing generic textbook answers. When analyzing a case study, candidates should follow a systematic approach. First, identify the business ownership type (sole trader, partnership, Ltd, PLC) and consider the typical objectives associated with that structure. Second, analyze the business life cycle stage (start-up, growth, maturity, decline) and assess whether objectives should prioritize survival, growth, profit, or restructuring. Third, examine financial data such as revenue, profit margins, cash flow, and market share to identify strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities. Fourth, consider stakeholder interests such as owners, employees, customers, suppliers, and the local community, recognizing that different stakeholders prioritize different objectives. Fifth, evaluate external factors such as economic conditions, competitive intensity, technological trends, and regulatory requirements that might influence objective setting. Finally, apply SMART criteria to proposed objectives, ensuring they are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound. For example, if a case study describes a sole trader running a local bakery with declining sales due to increased competition from a supermarket chain, a strong answer might recommend: "The bakery should set the objective of increasing customer retention by 25% within 12 months by launching a loyalty card scheme and hosting weekly community events, BECAUSE the case study shows that while footfall remains steady, repeat purchases have fallen by 30%, LEADING TO reduced revenue despite stable customer numbers, THEREFORE focusing on retention rather than acquisition will improve profitability without requiring significant marketing investment." This answer demonstrates contextual application, SMART criteria, and a clear chain of reasoning using the BLT structure.

The Role of Stakeholders in Objective Setting

Stakeholders are individuals or groups with an interest in the business's activities and performance, and their competing demands significantly influence objective setting. Owners and shareholders typically prioritize financial objectives such as profit maximization, return on investment, and dividend payments. In a PLC, shareholders exert pressure through voting rights and the threat of selling shares, forcing management to prioritize short-term financial performance. Employees prioritize non-financial objectives such as job security, fair wages, career development, and safe working conditions. A business might set the objective of "reducing staff turnover by 15% within 18 months by increasing wages by 5% and introducing a professional development program," recognizing that employee satisfaction drives productivity and reduces recruitment costs. Customers prioritize objectives related to product quality, value for money, customer service, and ethical practices. A business might set the objective of "achieving a 90% customer satisfaction rating within 12 months by improving response times and offering a 30-day money-back guarantee." Suppliers seek stable, long-term relationships and timely payments, leading businesses to set objectives such as "paying all supplier invoices within 30 days to maintain strong relationships and negotiate volume discounts." Local communities are concerned with employment, environmental impact, and corporate social responsibility, leading businesses to set objectives such as "creating 50 new jobs within two years and reducing waste sent to landfill by 40%." Government and regulators impose legal and compliance requirements, forcing businesses to set objectives such as "achieving full compliance with new data protection regulations by the end of Q2 2026." Examiners expect candidates to recognize that objective setting involves balancing these competing stakeholder interests, and that businesses must prioritize certain stakeholders depending on their ownership structure, values, and strategic priorities.

Exam Technique: The BLT Structure

The BLT structure (Because, Leading to, Therefore) is a powerful framework for building chains of reasoning that earn AO3 analysis marks. Many candidates make the mistake of stating a benefit without explaining the mechanism, resulting in descriptive rather than analytical answers. The BLT structure forces candidates to link cause and effect explicitly. For example, a weak answer might state: "The business should set the objective of reducing costs because this will increase profit." This is too simplistic and lacks depth. A strong answer using BLT would state: "The business should set the objective of reducing operational costs by 12% within 18 months through supplier renegotiation and process automation, BECAUSE the case study shows that the business's profit margin of 6% is below the industry average of 10%, LEADING TO reduced competitiveness and limited funds for reinvestment in marketing and product development, THEREFORE cost reduction will improve margins, enabling the business to invest in growth initiatives and strengthen its market position." This answer demonstrates a clear chain of reasoning: it identifies the problem (low profit margin), explains the mechanism (cost reduction improves margins), and links the outcome to broader strategic benefits (reinvestment and competitive strength). Candidates should practice applying the BLT structure to a range of question types, ensuring that every analytical point is fully developed and explicitly linked to the case study context.

Named Example Bank

Examiners reward candidates who reference real-world businesses to illustrate concepts, demonstrating commercial awareness and the ability to apply theory to practice. Here are five detailed named examples relevant to business aims and objectives:

-

Greggs PLC (UK Bakery Chain): Greggs is a publicly listed company operating over 2,300 shops across the UK. In recent years, Greggs shifted its objectives from traditional bakery products to include vegan and healthier options, setting the objective of "increasing sales of plant-based products by 20% within two years." This objective reflects changing consumer preferences and regulatory pressure to reduce environmental impact. The introduction of the vegan sausage roll in January 2019 generated significant media attention and contributed to a 13.5% increase in like-for-like sales in 2019, demonstrating how well-aligned objectives drive commercial success.

-

Patagonia (Outdoor Clothing Company): Patagonia is a private company renowned for prioritizing environmental sustainability over profit maximization. Founder Yvon Chouinard set the objective of "donating 1% of sales to environmental causes annually," later increased to "donating 100% of profits to environmental causes" following a 2022 ownership restructure. This non-financial objective conflicts with traditional profit maximization but has strengthened brand loyalty among environmentally conscious consumers, demonstrating that non-financial objectives can drive long-term commercial success.

-

Amazon (Global E-Commerce and Technology PLC): Amazon's founder Jeff Bezos famously prioritized long-term growth and market share over short-term profit, setting objectives such as "achieving market dominance in e-commerce by reinvesting all revenue into infrastructure, technology, and customer acquisition." For many years, Amazon reported minimal or negative profits despite massive revenue growth, as it prioritized the objective of "capturing the largest possible market share to create barriers to entry for competitors." This strategy eventually delivered enormous shareholder value, illustrating how objectives evolve over the business life cycle.

-

Timpson (UK Shoe Repair and Key Cutting Chain): Timpson is a private family-owned business that sets non-financial objectives related to employee welfare and social responsibility. The company has the objective of "employing ex-offenders, with 10% of the workforce comprising individuals with criminal records." This objective reflects founder John Timpson's belief in second chances and social impact, and it has generated positive media coverage and customer loyalty, demonstrating that non-financial objectives can enhance reputation and commercial performance.

-

Tesla Inc. (Electric Vehicle Manufacturer PLC): Tesla's mission statement is "to accelerate the world's transition to sustainable energy," reflecting a non-financial aim of environmental sustainability. However, as a publicly listed company, Tesla also faces pressure to deliver financial objectives such as "achieving profitability and positive cash flow to satisfy shareholders and maintain share price." CEO Elon Musk has set ambitious objectives such as "producing 20 million electric vehicles annually by 2030," balancing growth, sustainability, and shareholder value. This illustrates the tension between non-financial aims and financial objectives in PLCs.

Quick Summary

- Aims are broad, long-term goals (survival, profit, growth, market share); objectives are specific, measurable targets that operationalize aims using SMART criteria (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-bound).

- Financial objectives focus on profit, sales revenue, ROI, and market share; non-financial objectives focus on social responsibility, environmental sustainability, customer satisfaction, and employee welfare.

- Sole traders prioritize survival, work-life balance, and personal satisfaction; partnerships prioritize profit sharing and growth; private limited companies prioritize profit maximization and market share; PLCs prioritize shareholder value and market dominance.

- Objectives often conflict, requiring trade-offs between profit and ethics, growth and work-life balance, short-term profit and long-term sustainability, and market share and profit margins.

- Objectives evolve over time in response to business life cycle stages (start-up, growth, maturity, decline) and external factors (economic conditions, regulation, competition, technology).

- Context is critical: always apply objectives to the specific business ownership type, financial position, market conditions, and stakeholder interests described in the case study.

- Use the BLT structure (Because, Leading to, Therefore) to build chains of reasoning that earn AO3 analysis marks by explaining mechanisms and linking cause to effect.