Study Notes

Overview

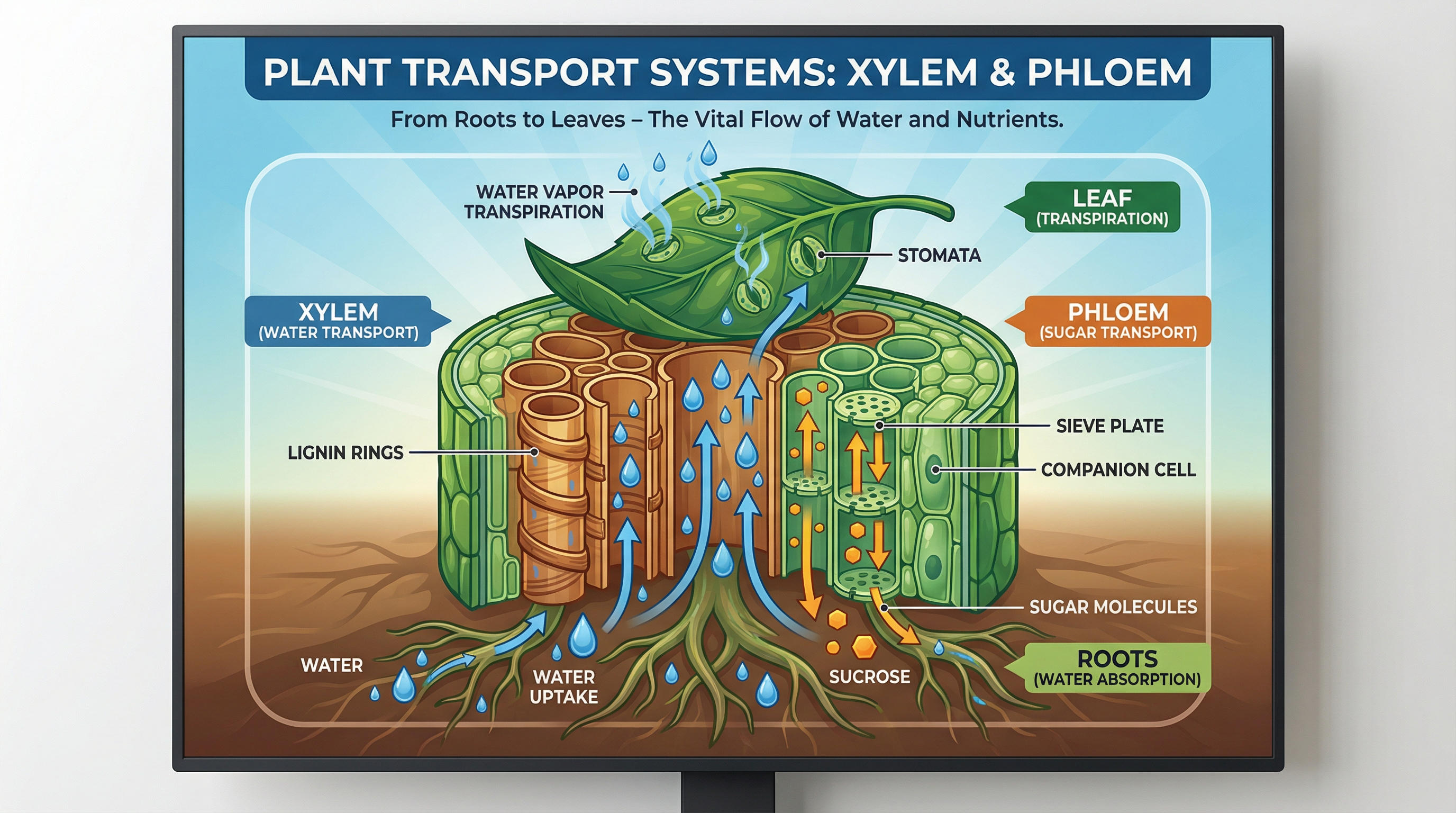

Welcome to the fascinating world of plant transport! This topic, officially known as Topic 6 in the Edexcel GCSE Combined Science specification, is all about the clever ways plants move essential substances around their bodies. Think of it as the plant's internal plumbing and delivery service. We'll explore the two main transport tissues, xylem and phloem, and understand how they are perfectly adapted for their jobs. We'll also delve into transpiration, the process by which plants lose water, and how environmental factors can change the speed of this process. Mastering this topic is not just about memorizing facts; it's about applying physical principles like diffusion and evaporation to biological systems. Examiners love to ask questions that test your ability to link structure to function and explain how different factors interact. Expect to see a mix of short-answer questions asking for definitions and longer, 6-mark questions that require you to compare and contrast the transport systems.

Key Concepts

Concept 1: Xylem - The Water Superhighway

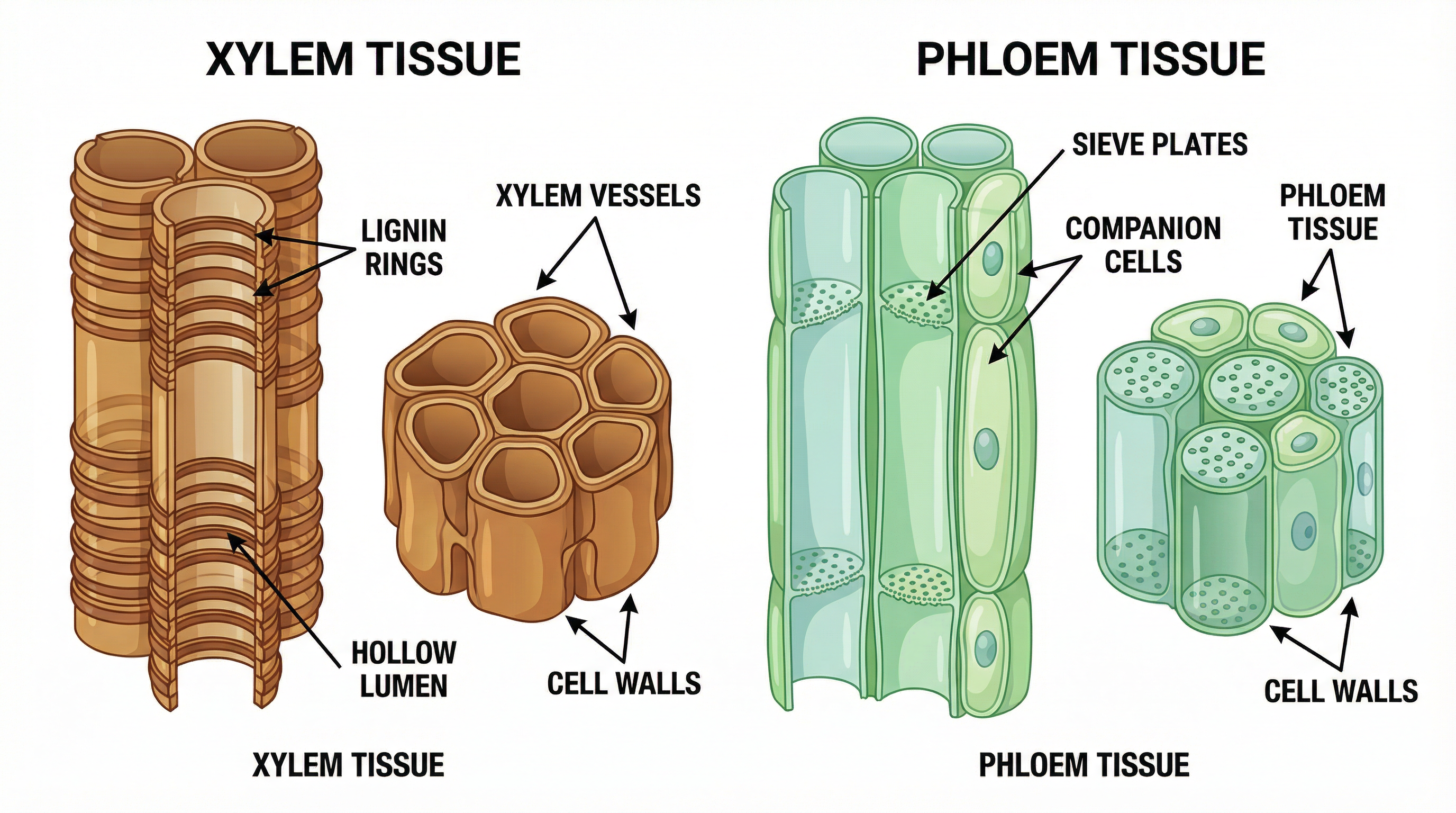

Xylem tissue is the plant's primary water-carrying system. Its job is to transport water and dissolved mineral ions from the roots, where they are absorbed from the soil, up to the rest of the plant, especially the leaves for photosynthesis. The structure of xylem is a perfect example of adaptation for function. Xylem vessels are made of cells that are dead at maturity. This is a key point that earns marks. Because the cells are dead, they have no cytoplasm, nucleus, or vacuoles, creating a completely hollow, uninterrupted tube called a lumen. This allows water to flow in a continuous column. The cell walls are thickened with a tough, waterproof substance called lignin. Lignin provides mechanical strength and support to the plant, preventing the vessels from collapsing under the negative pressure of water being pulled upwards. This process of water movement through the xylem is known as the transpiration stream.

Example: Imagine trying to drink from a straw. The straw is like a xylem vessel. If the straw was full of blockages (like organelles in a living cell), it would be very difficult to draw liquid up. The hollow nature of xylem makes it an efficient pipe for water transport.

Concept 2: Phloem - The Sugar Delivery Service

Phloem tissue is responsible for transporting dissolved sugars, primarily sucrose, from the leaves (where they are made during photosynthesis) to other parts of the plant where they are needed for energy or storage. This process is called translocation. Unlike xylem, phloem is a living tissue. It is composed of two main cell types: sieve tube elements and companion cells. Sieve tube elements are long, thin cells arranged end-to-end. The end walls between these cells have pores, creating sieve plates, which allow the sugary sap to flow through. Sieve tube elements lose their nucleus and most of their cytoplasm at maturity to maximize space for transport. However, they need to stay alive to function. This is where the companion cells come in. Each sieve tube element has a companion cell right next to it, which contains a nucleus and all the other organelles. The companion cell carries out all the metabolic processes needed to keep the sieve tube element alive.

Example: Think of a busy delivery company. The sieve tube is the delivery truck, and the companion cell is the driver and logistics manager, providing the energy and direction for the journey. Translocation in the phloem is bidirectional, meaning sugars can be transported both up and down the plant, from a source (like a leaf) to a sink (like a root or a growing flower).

Concept 3: Transpiration - The Inevitable Consequence

Transpiration is the loss of water vapour from the plant, primarily through small pores on the leaf surface called stomata. It is a consequence of the plant opening its stomata to take in carbon dioxide for photosynthesis. The process occurs in two main stages: first, water evaporates from the surface of the moist mesophyll cells inside the leaf. Second, this water vapour diffuses down a concentration gradient from the air spaces within the leaf out into the drier surrounding air. This loss of water from the leaves creates a tension or pull, known as the transpiration pull, which draws more water up from the roots through the xylem. This continuous flow of water is the transpiration stream.

Mathematical/Scientific Relationships

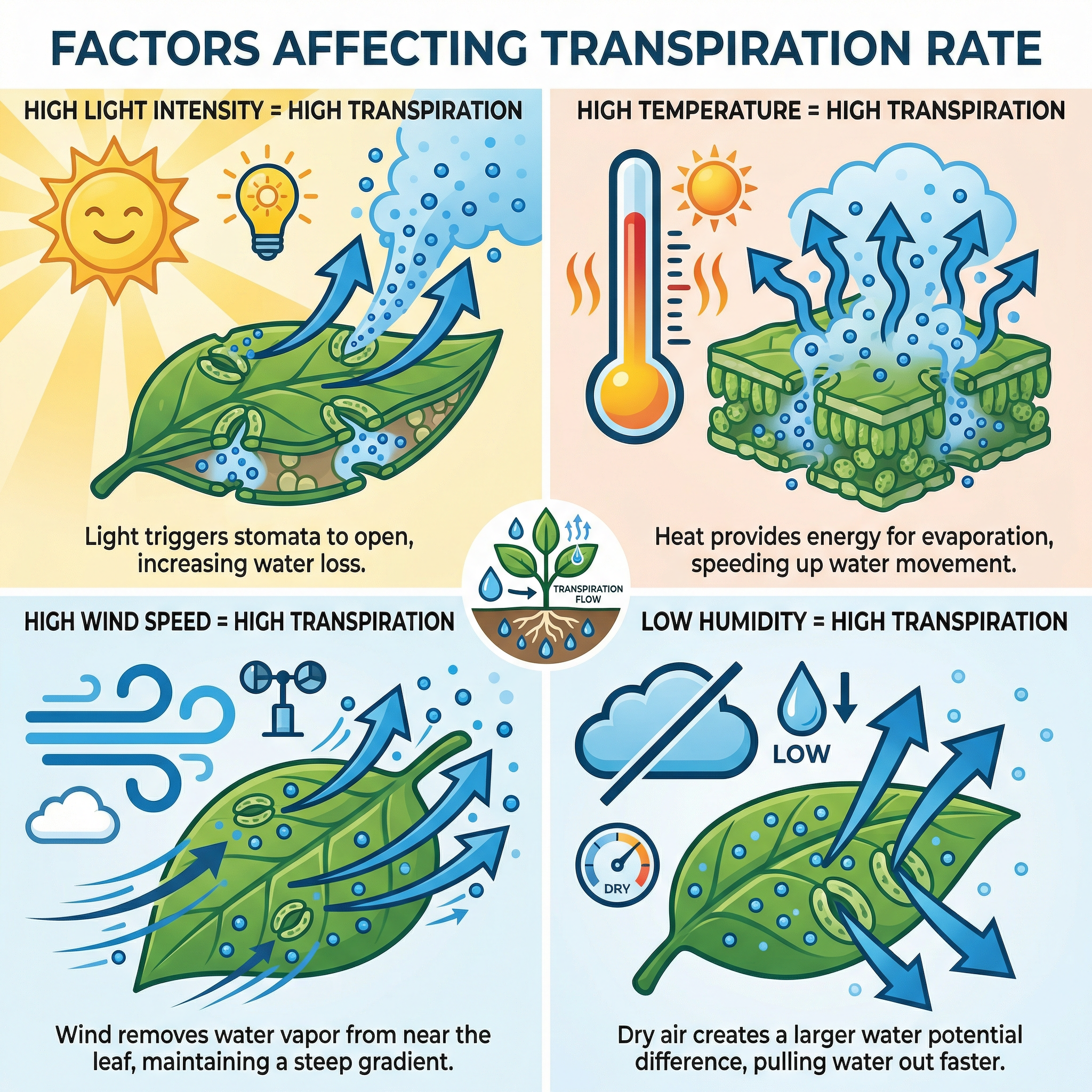

While you don't need to memorize complex formulas for this topic, you do need to understand the relationships between environmental factors and the rate of transpiration. You might be asked to interpret data or graphs related to these factors.

- Rate of transpiration is often measured as the volume of water lost per unit time (e.g., cm³/min) or the distance a bubble moves in a potometer.

- Relationship: The rate of transpiration is directly proportional to light intensity, temperature, and wind speed, and inversely proportional to humidity.

Practical Applications

This topic is directly linked to a required practical: investigating the effect of environmental factors on the rate of transpiration using a potometer. A potometer is a piece of apparatus that measures the rate of water uptake by a leafy shoot. It doesn't directly measure transpiration, but it gives a very good estimate because we assume that almost all the water taken up is lost through transpiration.

Apparatus: Potometer, leafy shoot, beaker of water, stopwatch, lamp, fan, plastic bag.

Method:

- Cut a leafy shoot underwater to prevent air bubbles from entering the xylem.

- Assemble the potometer underwater, filling it completely with water.

- Fit the shoot into the rubber tubing, ensuring a watertight seal.

- Remove the apparatus from the water and allow the shoot to acclimatise.

- Introduce a single air bubble into the capillary tube by lifting the end out of the beaker of water for a moment.

- Measure the distance the bubble moves along the scale in a set period of time (e.g., 5 minutes). This is the rate of water uptake.

- To investigate a factor, change the condition (e.g., move a lamp closer to change light intensity) and repeat the measurement. Keep all other conditions constant.

Common Errors: Getting air bubbles in the xylem when setting up; not ensuring the apparatus is airtight; not allowing the shoot to acclimatise before taking readings.